(Part 1 of 2)

We begin the story of Lucy Isabelle Pauling, Linus Pauling’s mother, with Linus Wilson Darling, Belle’s father and Linus Pauling’s maternal grandfather.

In 1863, Linus Wilson Darling’s father abandoned his family in Collingwood, Ontario, leaving his wife to struggle financially on her own. As a result, she sent her four eldest children, including Linus, to a foster home in New Jersey. When he was fifteen, Linus ran away from this home and made his way to Chicago, where he both worked and lived in a bakery. From there, he set out west, eventually settling near Salem, Oregon, and began teaching high school.

One of his students was Alcy Delilah Neal. The two began courting and were married in 1878. As they moved around Oregon, looking for a place to settle, they began having children. Their second daughter, Lucy Isabelle “Belle” Darling was born on April 13, 1881, while the family was living in Lonerock, a tiny town in eastern Oregon.

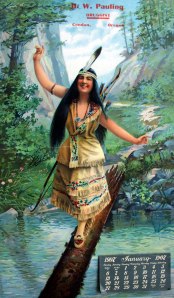

The family had arrived on hard times there and were, in fact, facing starvation. But they were saved when Linus bet his saddle against fifty dollars on Grover Cleveland to win the upcoming presidential election over James G. Blaine. Funded by those winnings, they moved twenty miles northwest, to Condon, where Linus opened up the town’s first general store selling patent medicines and running the post office – enough to keep him a busy man.

Three years after moving to Condon, when Belle was seven, her mother Alcy gave birth to a stillborn son. Badly injured by the traumatic birthing process, Alcy also passed away, one month later.

Linus however continued to lead a busy life. As he began to study law he occasionally hired a woman to help take care of the household, but mostly left it up to his four daughters – Goldie, Belle, Lucile and Abigail, all born in a span of five years – whom he called the “Four Queens.” (A fifth queen, Florence, was at the time too young to pitch in.) The bulk of this work often defaulted to the oldest daughter, Goldie.

Linus eventually remarried, finding a younger widow who owned a large wheat farm and an extra ten thousand dollars to her name. This new-found financial support allowed Linus to become a gentleman farmer and begin his law practice.

For Belle, this period was one of contrasts. Her mother gone, the household responsibilities mounting, and her father mostly a distant man, she began suffering from bouts of depression. On the other hand, her new family’s wealth and large home made her one of the Condon elite as a teenager.

Indeed, the family resources offered some measure of protection from the economic depression plaguing the country, and the family was occasionally able to take shopping trips to Portland for dresses and other fineries unavailable in the small farming town. In 1895, Belle and Goldie also took advantage of the opportunity to attend boarding school at Pacific University in Forest Grove, Oregon. Belle did fairly well academically, earning marks of 85 in Bible, 91 in grammar, and 98 in arithmetic. But she did not enjoy the boarding school experience and came back to Condon after her first term. Her older sister, Goldie, was able to make it through the rest of the year before coming home.

Returned to Condon, Belle slipped anew into her role as one of the town’s elite young women. One day, in the fall of 1899, Goldie invited the seventeen-year-old Belle over to her home, to meet Condon’s new druggist, Herman Pauling. Herman quickly earned the respect of the town and was the guest of honor at several dinners and dances. At these events, he and Belle often ended up talking with one other. The more time they spent together, the closer the two became, and by Christmas of the same year, they were engaged to be married the following May. Their lavish wedding was attended by nearly the whole town.

The fairy tale ended quickly, however, when Herman was forced to look for work: the investors backing his Condon pharmacy had pulled out, forcing Herman to search for a new job. Since the Condon area was not big enough to support Herman on its own, he and Belle moved to Portland, finding a residence near Chinatown.

Belle was eager to take advantage of the entertainment and shopping possibilities that had once only been accessible following a long trip from Condon. Yet she was pregnant before she and Herman had left Condon and on February 28, 1901, she gave birth to their first child, Linus, named for Belle’s father. Soon after the birth, Belle took Linus back to Condon to visit her family. While there, they both came down with an illness, but quickly recovered and were back in Portland by May.

Linus was quickly followed by his first sister, Pauline, born in August 1902. Frances Lucile (or “Lucie,” named after one of Belle’s favorite poems by Owen Meredith) arrived on New Year’s Day 1904.

When Herman found a job as a traveling salesman, Belle was frequently left alone to care for the children. Her unquenched desire to enjoy the city, her absent husband, and her mounting responsibilities as a parent all combined to engender a growing resentment. Frustrated, she repeatedly wrote to her husband while he was on the road, admonishing him for not making enough money and spending so little time at home. Herman usually responded that he was doing all that he could to provide for Belle and the children, and that their future as a family would be brighter.

In 1904, attempting to arrive at this brighter future, Herman took a new job – one that still required travel but was based in Salem. His hope was that doing so would give him more time at home since Salem was more centrally located in the Willamette Valley. The job did not last long though, and Herman was soon searching for new opportunities. Once again, the family turned to old territory: Condon seemed promising as Herman could open up his own store there with the help of Goldie’s husband. And so it was that, in April of 1905, with Herman already ahead of them, Belle packed up the remainder of their belongings and moved with the children to her old hometown.

A group photo including the Pauling children: Pauline (front row left), Lucile (front row right) and Linus (back row right). 1906.

The Paulings’ new home was above the general store that belonged to Goldie’s husband, Herbert Stephenson. Here, little Linus was free to roam around the town, while Belle stayed at home looking after her daughters. During the harvest period, Belle would also help at the Stephenson wheat farm by cooking for all the temporary workers brought in to process the grain.

Moving to Condon meant that Herman was always close by and that he made a good income, albeit with a brief interlude of lean times caused by yet another national financial depression. Condon was able to bounce back due to its rising population of homesteaders taking advantage of the free 320 acres being offered by the federal government, a boon that combined nicely with a run of increased wheat harvests and the addition of a Northern Pacific rail spur. Nonetheless, Belle was not happy in Condon: Herman was still working over twelve hours a day, she missed the culture and excitement of Portland, and the summers were unbearably hot. The latter two issues were solved, at least in part, by annual summer trips to the milder Portland suburb of Oswego, where Belle and the children stayed with Herman’s parents.

While visiting Oswego in the summertime allowed Belle to take in events like the centenary celebration of the Lewis and Clark expedition, she did not like being away from Herman. Letters to her husband sent during this period are full of anxiety over Herman’s fidelity and the family’s financial situation. By the end of the summer of 1909, Belle had convinced Herman that the family should move back to Portland, though Herman did not need too much convincing on his part, as he was also ready to leave behind the heat and petty small town politics.

The family moved to East Portland, where Herman opened up another drugstore in a fast-growing neighborhood. Again he worked long hours, leaving Belle to take care of the children. But Belle also took advantage of being back in Portland by enrolling in German classes at a nearby high school. Since Herman’s business was slow to start, he used his free time to study German as well, providing Belle and Herman with a rare leisure pursuit that they could share as a couple.

The happy times were not destined to last. In April 1910, the dark clouds began to gather when Belle’s father passed away. While Belle had never been particularly close with her dad, his passing was still difficult for her.

Three months later, Belle, her sisters, and their children were attending the Rose Festival in Portland and when they returned they found Herman at home in tremendous pain. Herman’s stomach aches, the result of an ulcer, were a recurrent issue for him, but they had never struck so severely. The attack, as it turned out, was fatal – he died soon after they returned. Belle was emotionally devastated, financially imperiled and, widowed with three children, staring at a very uncertain future.

Filed under: Pauling and Oregon | Tagged: Belle Pauling, Condon, Herman Pauling, Linus Wilson Darling, Lucile Pauling, Pauline Pauling, Portland | Leave a comment »