[An excerpt from Ava Helen Pauling: Partner, Activist, Visionary, by Dr. Mina Carson – now available from the Oregon State University Press.]

Like her letters to her global correspondents, Ava Helen’s paper on women, “The Second X Chromosome,” used simple language to deliver a confident and impassioned assertion that it was time for all women to receive the equal standing and opportunities to which, in many places, their legal status already entitled them. Following her initial drafts through her final typed presentation for distribution, it is evident that she wrote easily when she was excited, in many cases framing the ultimate argument in her first handwritten draft. Linus too contributed to the paper, although his surviving notes addressed not rhetoric, but background research that he or Ava Helen thought would be helpful: information about Jane Addams, Bertha von Suttner, and other figures she introduced in the body of the paper.

She indicted American hypocrisy.

While her legal and social status under law are now more or less secure in most parts of the world, discrimination against women is still very real and nowhere more than in the United States which lags woefully behind the more advanced Western Nations and indeed in many respects behind the socialist countries in equality for women.

Whereas women were admitted to Soviet medical schools strictly on the basis of “scholastic ability,” she said, “in the United States … the ratio of women to men in medical schools is smaller than in 1900.” Perhaps in a nod to her more conventional audience, she joked that while Japanese women were often cited as the “ideal of complete subjection to men,” at least a woman walking behind her husband could keep an eye on him.

Ava Helen’s use of genetic imagery (“the second X chromosome”) to frame her argument exemplifies not so much an essentialist position on women’s special nature – although she could never quite separate herself from that possibility – as a Jane Addams-like strategy of promoting a “both-and” philosophy of equal opportunity. Like Addams fifty years earlier, Ava Helen skirted essentialism (the “nature” of women) by discussing women’s social and cultural roles throughout history – even prehistory.

She argued that, because of their role in carrying the embryo, the earliest women were undoubtedly “observant, wary, cautious, and persevering”: the first scientists, as they figured out how to feed and warm their families. Some anthropologists saw women as the stabilizing force in society, as they established agriculture, fire, and private property under primitive matriarchies. Ava Helen argued that historically, as her indispensable skills were recognized, woman fell victim to male efforts to keep her “under subjection.” Ten thousand years ago, matriarchy gave way to patriarchy “and women returned to the status of chattels.”

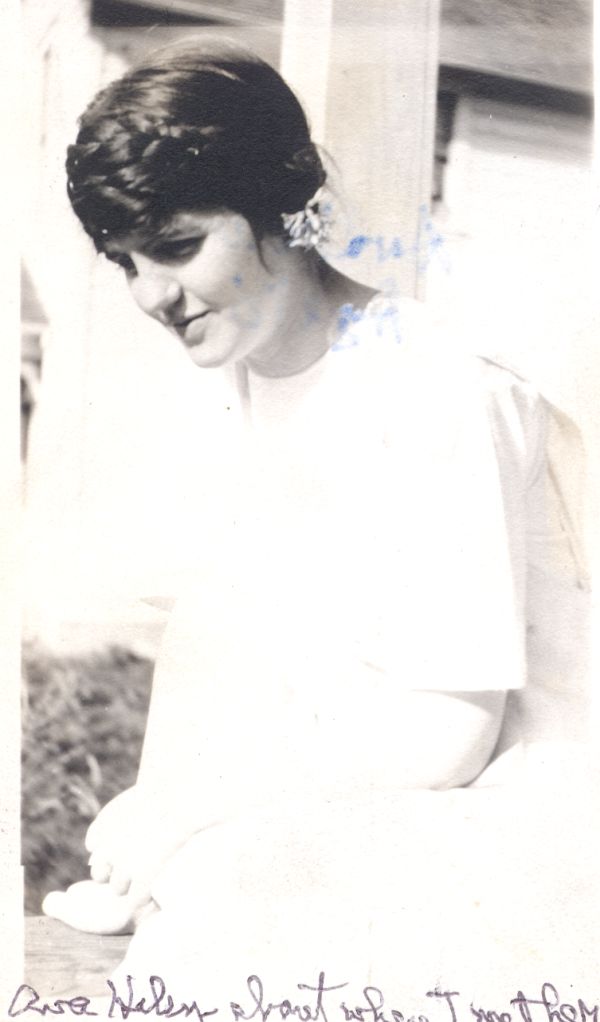

Ava Helen Pauling, 1958.

Only in the last two hundred years, she argued, had patriarchy faced new challenges. Women had written two of the nineteenth-century novels that successfully changed social perceptions of great injustices: Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin and Bertha von Suttner’s Die Waffen Nieder [Lay Down Your Arms, or as Pauling translated it, Down with the Weapons of War]. In the twentieth century, Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring and Jessica Mitford’s The American Way of Death likewise analyzed the social and environmental infrastructure:

In each of these four books the author, a woman, is attacking and exposing a well entrenched economic asset of society in areas controlled completely by men, eg. slavery, war, poisonous chemicals, and the funeral industry.”

Ava Helen brought her no-nonsense brand of political argument, fronted by her stance against interventionist warfare, to her position on modern feminism. She was not a fan of Betty Friedan’s recent Feminine Mystique, which, she wrote to a friend, “has some very foolish ideas in it.” She indicted Friedan for blaming the inability of American POWs in Korea to withstand their imprisonment on their permissive, smothering mothers. Pauling had no patience for an analysis predicated on the legitimacy of America’s military engagement in Korea. “I won’t agree,” she asserted, “that a woman’s highest role is to teach her sons to fight nobly the kind of war that was fought in Korea.” One can imagine the L. A. Unitarians nodding at this point.

Coupled with her disdain for Friedan’s tacit acceptance of the normality of the Korean War, Pauling resisted the invidious distinction between housewife-mothers and women who worked outside the home. “[W]ere the brave, napalm bomb throwing heroes of the Korean War the sons of career women? This would make an interesting study.” She went on:

A way to verify the Feminine Mystique would be to conduct a survey among women who work outside the home and compare them to women who work within the home with regard to happiness, contentment, joy of life, and adjustment to family and friends. I believe such a survey would show that work outside the home is not the answer to the American woman’s dissatisfaction and unhappiness. It is an oversimplification of the problem. Many women who work outside the home are just as unhappy as women who don’t.

The answer: equal access to college education; equal weighting of professional and household labor; public nurseries to allow mothers as well as fathers to go to school or work outside the home; and women’s active participation in politics.

Ava Helen Pauling, August 1964.

Ava Helen’s feminist reform philosophy reflected her immersion in the Women Strike for Peace movement, whose primary image was that of active mothers protesting on behalf of the generation they were carrying in their wombs and raising, but whose most powerful spirits were women in their thirties, forties, and fifties, veterans of other peace movements, some of whom still had children at home and others of whom were primarily professionals.

Pauling’s evolving philosophy also offered her a way to resolve her own existential dilemmas. She had put her college education aside to marry and bear four children. Her identity for twenty years was the wife who protected her husband’s creative and intellectual life from family demands. Yet she had also excelled in chemistry as well as language and social science at Oregon Agricultural College. She had left her first toddler and a brief manual on modern child rearing in her mother’s hands in order to tour Europe with her husband unencumbered by maternal responsibilities. She had tutored her husband in social justice issues during the Depression of the 1930s. She had plunged into political work as Europe collapsed again into bloody war, and then as the United States imprisoned American citizens on suspicion of hostile loyalties. She had inspired Linus’s activism after the war to help fellow Americans understand the dire implications of the United States’ development of nuclear weapons, and over the following decade had stayed by his side as he risked his career against panels of accusers and political adversaries. And from the mid-1950s on, she had accepted her own career as a peace activist, her skills as a strategist, networker, and speaker enhanced by her notoriety as Linus’s wife and his partner in the petition drives that ultimately earned him the peace prize.

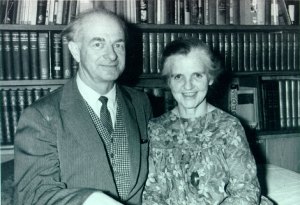

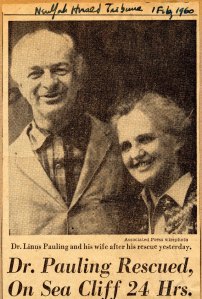

The Paulings at Deer Flat Ranch, 1962. Photo by Arthur Dubinsky.

Her friend Corda Bauer picked up on Ava Helen’s ambivalence as part of a snapshot Ava Helen sent her along with the manuscript of her “Second X Chromosome” paper. The photograph shows the Paulings at their ranch, with Linus in the foreground leaning on a fence, and Ava Helen slightly behind him. Bauer requested permission to ask an “impertinent” question:

Was it design or chance that kept you in the background of the photo? As an advocate of women’s rights I would have liked to have seen you leaning on the fence too, in an attitude of secure accomplishment. Linus deserves the place between the gateposts, where he can come and go as he pleases. Had you sat on top of the fence, it would have symbolized that women have to overcome many hurdles, but by golly no mere fence is going to stop them.

She was Linus’s equal, yet a step behind him, like the Japanese women Ava Helen had joked about. Linus Pauling, Jr., remembers that by the 1970s – and perhaps earlier – Ava Helen had started aiming sharp comments at Linus as they went about their daily routine. He remembers hearing her mutter that she too might have won a Nobel prize had she not been busy keeping the house and raising the children. This memory probably does not detract from the other things we think we know about the Paulings’ marriage: that the couple shared an unusual intimacy; that they preferred being together to being apart; that within the walls they were colleagues in their peace activism; that Linus always credited Ava Helen for her inspiration and companionship during the years of peace work; that he was most likely not a tyrant behind closed doors. From the year of courtship through his distracted grief after her death in 1981, Linus held Ava Helen as the most precious force in his life. “When asked to name someone else in the United States who might merit recognition for his efforts towards peace,” said Wallace Thompson during a Nobel celebratory dinner, “Dr. Pauling unhesitatingly said: ‘My wife.'”

The Paulings with Mrs. Dubinin at the 7th Pugwash Conference, Stowe, Vermont, 1961.

Nonetheless, in the early years of marriage she suffered the decentered isolation of virtually all stay-at-home parents. This was exacerbated by Linus’s early and persistent fame, and his multiple scientific commitments. After the first few years of their marriage, she could not keep up intellectually with his work, and that must have added another dimension to any resentment she felt at her position in their life together.

Did she encourage their peace work in order to climb to an equal footing with him in their marriage, and in the world’s eyes? If she harbored that motivation, it really seems to have been obscured by her genuine passion for political change, coupled with her anxiety for Linus to be as effective as possible in his advocacy work. Yet by the early sixties, as she received multiple invitations to speak to progressive groups and women’s groups, and as she established a position as a key consultant among peace advocates, as she was for the WSP founders and Canada’s VOW activists, she also articulated her feminist vision of the equal value of all kinds of labor, professional or domestic, paid or unpaid, as well as the power of women to move the world politically. Rosa Parks, Rachel Carson, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Bertha von Suttner – all applied their personal and intellectual power to identify and redress social wrongs. Corda Bauer understood Ava Helen’s core message when she compared her friend’s talk to Camilla Anderson’s assertion in Saints, Sinners and Psychiatry: “Once women have tested their strength and overcome their rebellion, they are then free to return to homemaking and bringing up children with love and understanding by choice rather than being forced into it.”

Ava Helen Pauling: Partner, Activist, Visionary is available for purchase from the Oregon State University Press.

Filed under: Ava Helen Pauling | Tagged: Ava Helen Pauling, Bertha von Suttner, Betty Friedan, Corda Bauer, feminism, Jane Addams, Linus Pauling, Mina Carson | Leave a comment »