Linus Pauling’s colleague and friend, Frank Press, passed away last month on January 29, 2020 in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. Press was 95 and died of complications from a fall. Perhaps most widely known for his work as President Jimmy Carter’s chief science advisor and his twelve years leading the National Academy of Sciences, Press also collaborated with Pauling on multiple fronts, and the two ultimately grew close.

Press was born on December 4, 1924 in Brooklyn, New York. After earning his bachelor’s degree at City College of New York in 1944, Press went on to Columbia University where he earned a master’s (1946) and a Ph.D. (1949) in geophysics. During that time, Press married his high school sweetheart, Billie (nee Kallick), and the couple remained together until Billie’s death of heart failure in 2009.

After a few years teaching at Columbia, Press was offered a professorship at the California Institute of Technology, where he remained until 1965. Press left Pasadena for a position as chair of earth and planetary sciences at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and remained at MIT until he was asked to serve as President Carter’s science advisor and director of the Office of Science and Technology Policy.

Not long after Carter was voted out of office, Press was selected to serve as president of the National Academy of Sciences, where he remained until 1993. Following this, he took up a four-year fellowship with the Carnegie Institute as the Cecil and Ida Green senior research fellow in the Department of Terrestrial Magnetism. His fellowship concluded, Press remained on the Carnegie board for another ten years.

Press’ long and fruitful career brought him into contact with Pauling on many occasions. They first met at Caltech, but did not have cause to interact very frequently, owing to their different departmental affiliations and research agendas. The two began to find a bit more common ground through their shared interest in social justice issues concerning the United States and the Soviet Union. Like Pauling, Press pushed for both nations to sign the partial test ban treaty in 1963. Later, Pauling and Press spoke out to protest the USSR’s treatment of scientist and dissident Andrei Sakharov.

Indeed, shared interest in Sakharov seems to have prompted one of their first formal interactions, a 1983 telegram from Pauling informing Press that he had offered a job to their Russian colleague. Even though the offer did not appease the Soviets enough to release Sakharov, the telegram did catch Press’ attention. Perhaps influenced by Pauling’s actions, the National Academy of Sciences, led by Press, formally renounced the Soviet government’s mistreatment of Sakharov, and refused to participate in a joint US-Soviet scientific cooperation in 1984.

Though Press and Pauling were not successful in securing Sakharov’s release, their shared effort on this issue created space for the two to form a friendship. As president of the National Academy of Sciences, Press sent Pauling a card nearly every year of his tenure, and Pauling become close to Billie Press as well. The friendship between the three was such that Billie often included her own note in the annual holiday card, at one point thanking Pauling for his gift of Florence Meiman White’s book, Linus Pauling Scientist and Crusader. When Pauling announced that he had cancer in 1992, the news shocked the Presses, though they were heartened to learn that he had been well enough to celebrate his 91st birthday with sixteen of his closest friends and family.

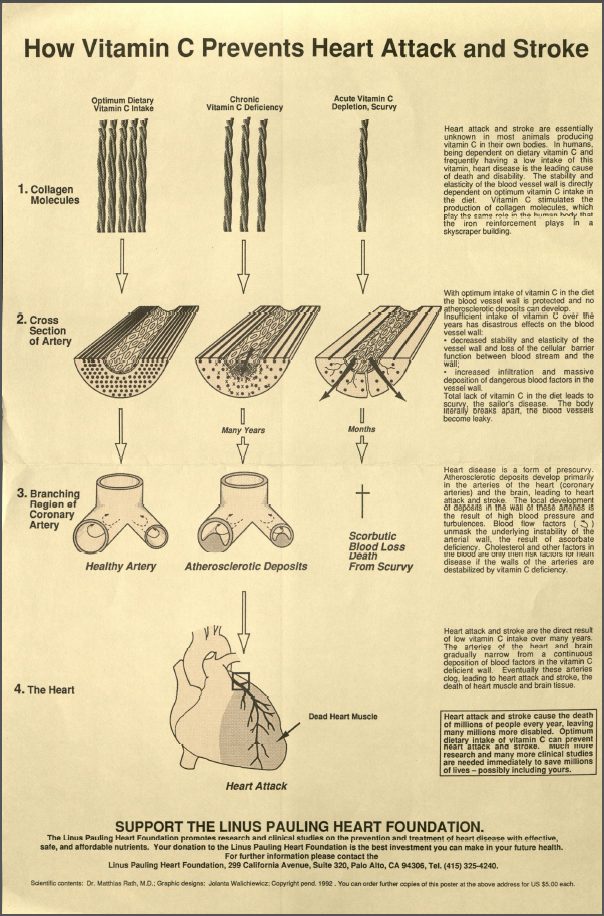

Pauling was also concerned with the well-being of the Presses, and it was here that friendship and current research intersected. As his work on orthomolecular medicine moved forward, Pauling was increasingly convinced that the Federal Recommended Daily Allowance (RDA) for certain vitamins, such as vitamin C, were far too low. Pauling believed the RDA should be much higher, and that a higher intake of vitamin C could drastically reduce the chance of developing cardiovascular disease, among other maladies.

Pauling was so convinced of this idea that he took pains to let his friends know that they could easily reduce their risk of heart disease by following the simple step of increasing their vitamin C intake. With this concern in mind, Pauling wrote to Press to urge him and Billie to have blood samples drawn so that their physician might determine the levels of lipoprotein (a) in their systems. Pauling specified that if either of their results came back elevated, “I strongly recommend that you begin a prophylactic regimen, that of taking some extra vitamin C and also perhaps 2 grams per day of L-lysin,” the latter because “the L-lysine interferes with the deposition of lipoprotein in the vascular wall.”

Pauling was also quite willing to review their results. “If the level is high,” he wrote, “there are orthomolecular measures that you should take. Let me know the results of the analyses, and I shall tell you what you ought to do.” Anticipating that the Presses might be nervous about vitamin C megadosing, Pauling wrote that a recent friend of his had used orthomolecular treatments to make a remarkable recovery after being bed-ridden following a third triple by-pass surgery. He signed the letter “Love From,” Linus Pauling.

From the correspondence, it appears as though Press trusted Pauling’s guidance. Shortly after receiving Pauling’s letter, Press replied that he would get his lipoprotein levels checked, and that he and his wife “appreciate[d] [his] interest in [their] well-being.” Press concluded the letter by noting the extent to which he and his wife “have admired you over the years.”

Several months later, in June 1992, Pauling asked Press for his help with an issue of mutual concern. Pauling’s request was spurred by an article that he had recently read titled “Reducing the Risk of Chronic Disease,” a summary of the National Research Council’s landmark, three-year study, “Diet and Health.” The aim of the study was to assist the public in making sound decisions related to their diet. (For one, the notion of “food groups” emerged from this study.)

Pauling called many of the study’s conclusions into question and, not surprisingly, took particular offense to a passage that read, “If you take a dietary supplement, do not exceed the U.S. Recommended Daily Allowance.” Because the statement was coming directly from the National Academy of Sciences, Pauling thought that he might be able to enlist Press’ support in revising its language. In his letter, Pauling was clear in his intent, writing that

I believe that this is an important matter – important to the health of nearly all Americans and other people. It seems clear to me that the members of the Food and Nutrition Board are biased against the optimum use of vitamins and are unwilling to consider the evidence. It is my duty as a member of the Academy to try and rectify this situation.

Pauling’s pleas did not fall on deaf ears. Shortly after receiving his letter, Press replied that he would pass Pauling’s concerns on to the Food and Nutrition Board (FNB) for their “thoughtful consideration” at their next meeting. Pauling’s timing could not have been better, Press explained, because the FNB had recently approved a study to look into nutrition requirements for older adults. As Press noted, this was partially due to Pauling’s inquiries into the “possible roles that antioxidant nutrients may play in preventing acute infections and chronic diseases.” Pauling passed away before the FNB had issued a verdict, but he surely took some degree of comfort at having been heard by his colleague and friend, Frank Press.

Filed under: Colleagues of Pauling | Tagged: Andrei Sakharov, Frank Press, heart disease, Linus Pauling, lipoprotein(a), National Academy of Sciences, orthomolecular medicine, vitamin C | Leave a comment »