Linus Pauling and others protesting the dismissal of H. Bruce Franklin, September 1971. Credit: Stanford University Libraries.

[The seventh and final post in our series on Linus Pauling’s association with Stanford University.]

In the wake of a series of heated and, at times, violent anti-war protests on and near campus, university president Richard W. Lyman moved to have tenured English professor H. Bruce Franklin dismissed from the Stanford faculty. In so doing, Lyman accused Franklin of having incited violence during a speech that he had given. Lyman also viewed Franklin as an enduring threat to others at Stanford.

Linus Pauling disagreed with this course of action and decided to question Lyman directly. In a handwritten note generated in preparation for remarks delivered to the Academic Senate, Pauling stressed that

The ‘misbehavior’ which he [Franklin] is accused was not in connection with his academic duties. It is my understanding that Professor Franklin has not been charged with misbehavior or neglect or malfeasance in connection with his teaching or other academic duties.

Neither did Pauling see “any credible justification” that Franklin was a threat to others. As such, Pauling concluding that Lyman’s case stood as “an extraordinary and unprecedented act of violation of the principles of academic freedom and individual rights – a really dangerous introduction of authoritarianism in the University.”

Pauling had also saved a copy of a letter that Franklin wrote to Lyman at the end of February 1971. In it, Franklin accused the president of using the press – and especially the Stanford University media apparatus – as a lever to turn Stanford’s faculty against him. Instead of taking this approach, Franklin felt that Lyman should issue his accusations directly, rather than operating in innuendos such as “acting in an unlawful manner” and “playing a role in tragic events.”

Franklin further noted that these vague charges, as issued by Lyman, would appear in affidavits submitted for his forthcoming court appearance, thus putting Franklin in a position that he characterized as “First the sentence, then the defense, and finally the charges.”

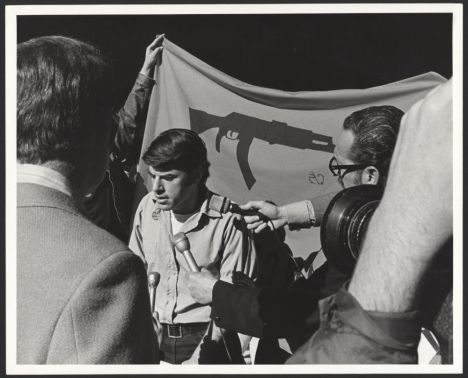

Bruce Franklin at a Stanford University demonstration, February 1971. Credit: Stanford University Libraries.

Franklin’s day before a judge came the next week, but he was not fighting a solitary battle. The day before, Pauling and fifty-four others had appeared in court on his behalf in an attempt to block an injunction that had been issued against him and over 1,000 others. Pauling and his colleagues argued that the injunction would have “no effect on the underlying causes of campus unrest. If anything, it may serve to hinder the analysis and correction of Stanford problems.”

The group further described their action as having been inspired by the lack of a response by academics against the Nazis in the 1930s. In tandem, over 100 members of the Academic Council at Stanford issued their own warning against Lyman’s actions, stating that his decrees would “create an institutional orthodoxy which makes ‘heretics’ out of those who disagree.”

The following day, Franklin made his appearance in court. A subsequent press release described a portion of Franklin’s closing argument in which he stated

I would say frankly that when I read of the bombing of the [U.S.] Senate yesterday [by the Weather Underground], I thought that that was a wonderful act and I understand that according to what is left of our rights in this country, that one supposedly has the right not only to believe that, but to say what I just said. The advocates of free speech are not prepared to allow free speech to people who think those thoughts and say those things… when a peaceful sit-in or advocacy of a strike is threatened as criminal behavior, the state teaches us a lesson – that our revolutionary analysis is correct and that at some time we should advocate immediate armed struggle against the state.

When the petition to the Advisory Board in support of Franklin was delivered at the end of April, faculty members also addressed the Academic Council on the matter. A statement that Pauling saved from this meeting described how faculty were most “concerned with the intimidating effect upon all of us, in carrying out our obligations to our consciences and to the University community, if the exercise of the First Amendment rights on this campus can be penalized by loss of tenure and dismissal.”

They likewise invoked the Nuremberg trials as a precedent to question Henry Cabot Lodge’s role in “criminal war policies,” and cited the First Amendment in support of Franklin having protested Lodge’s appearance at Stanford.

About a month later, with the situation at Stanford beginning to calm down, Pauling gave the commencement speech at the University of California, Berkeley, stressing his own commitment to the peaceful resolution of conflicts. In his address, Pauling stressed a basic belief system that had guided him for decades:

I believe that it is possible to formulate a fundamental principle of morality, acceptable by all human beings, and that this principle of morality can and should be used as a basis for making all decisions. The principle is this: that decisions among alternative courses of action should be made in such ways as to minimize the predicted amounts of human suffering.

In early June, at about the same time as Pauling’s speech, Bruce Franklin was formally suspended from Stanford without pay. That September, at the beginning of the next academic year, Pauling voiced his continuing objection to Franklin’s treatment by adding his name to a “Statement of Faculty Opposed to Political Firings.”

The statement not only addressed the Franklin affair, but also the firing of Sam Bridges, an African-American janitor at the Stanford Medical Center. In so doing, the statement connected the Franklin and Bridges incidents, noting that they were both “sharp reminders of the acute problems of racism and war” and arguing that “the time and energy of the University should be directed towards the solution of the problems, not toward the punishment of protesters.”

Pauling does not appear to have been as involved in the Bridges case, but he did save newspaper clippings and statements issued by Stanford Medical Center officials surrounding the April 1971 affair. According to a Stanford Daily article published after the incident, Bridges had been speaking with fellow employees about racist hiring policies at the medical center.

Specifically, Bridges told his colleagues that he had been prevented from advancing within the hospital while others from the outside had been brought in to fill vacancies for which he was qualified; vacancies that would have served as a step up the ladder for Bridges. Other employees responded with similar stories, and Bridges shared them as well. Not everyone that Bridges spoke with was sympathetic however, and some complained. Within a week of these complaints being issued, Bridges was fired without any possibility of submitting a grievance.

The Black Advisory Council at the medical center investigated the firing and found that there had been several complaints against Bridges for not doing his work and for being verbally abusive. Some of these statements were subsequently withdrawn, an action that precipitated an occupation of the medical center building with the occupiers calling for Bridges to be rehired.

Once the occupation had passed its thirtieth hour, police cleared the space using tear gas and by breaking down the door of the office in which the occupiers had sealed themselves. Afterwards, the medical center allowed Bridges to pursue grievance procedures. He chose not to pursue this option, believing that it would not lead anywhere productive. Instead, he devoted more of his time to coordination efforts with the medical center’s Black Worker’s Caucus.

While the Bridges affair resolved itself fairly quickly, Bruce Franklin’s case dragged into the next year. In January 1972, nearly a year to the day of his initial demonstration again Henry Cabot Lodge, the Faculty Advisory Board voted to formally dismiss Franklin, effective August 1972. With the assistance of the American Civil Liberties Union, Franklin attempted to fight the decision, but to no avail.

Pauling saved a March 1972 article from Science which reported that Franklin “hoped” for violence in response to his dismissal, and that arson and vandalism on campus had indeed followed. The article also quoted Pauling on the decision, which he described as “A great blow, not just to academic freedom, but to freedom of speech.”

Filed under: Peace Activism, Stanford University | Tagged: Bruce Franklin, Linus Pauling, peace activism, Sam Bridges, Stanford University, Vietnam War | Leave a comment »