Ken Hedberg performing in “The Road to Stockholm: The Appalling Life of Linus Pauling,” December 1954. Hedberg and other Caltech colleagues sang and danced on stage to celebrate Pauling’s receipt of the Nobel Chemistry Prize.

[Celebrating the life of Dr. Kenneth Hedberg (1920-2019), part 4 of 5.]

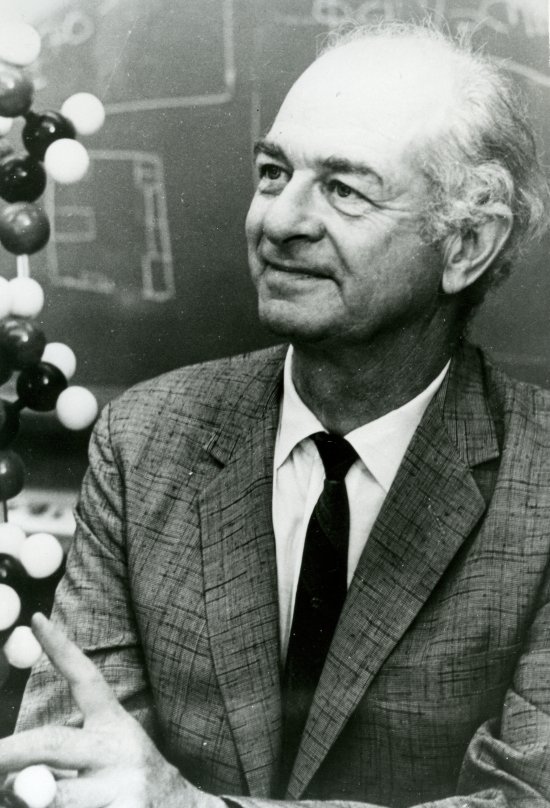

Though he left Caltech at the end of 1955, Ken Hedberg maintained a friendship with Linus Pauling that lasted for the rest of Pauling’s life. Despite their physical distance, the two kept an active correspondence and Pauling sometimes sent samples from his own research for Hedberg to run through his electron diffraction apparatus in Corvallis. Pauling also wrote multiple letters of recommendation in support of various fellowship applications submitted by his former student, frequently noting the many important contributions that Hedberg had made to the field of electron diffraction.

James Jensen, President of Oregon State University from 1961-1969.

Hedberg’s friendship with Pauling turned out to be especially fruitful for Oregon State University, because it was partially through his persistent efforts that the Ava Helen and Linus Pauling Papers made their way to OSU.

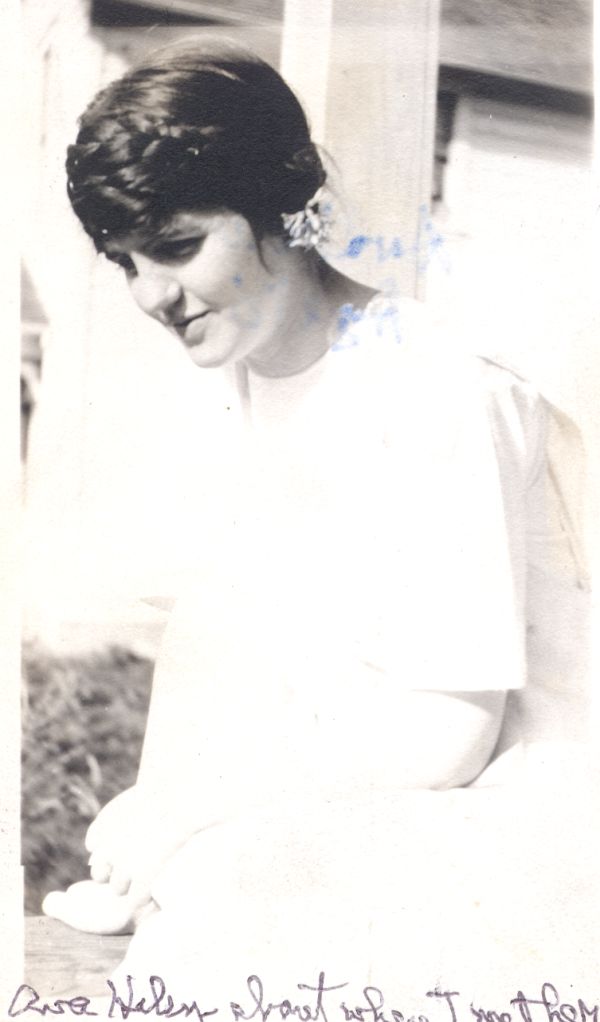

The story begins in the early 1960s, when Hedberg was chatting with Ava Helen Pauling at a banquet where they happened to be seated next to each other. During the course of the conversation, Ava Helen revealed that she and her husband had been pondering the question of what to do with their papers when they died, noting that they had received expressions of interest from several universities and other institutions. Although OSU was not among those courting the Paulings, Ava Helen felt that their alma mater was the right home for the materials and had run this idea past her husband. Though Linus had been embroiled in a rift with the university for most of the 1950s (over the firing of his former student, Ralph Spitzer, on political grounds), Ava Helen was now trying to convince him to “let bygones be bygones” and renew his bond with Oregon State.

Ava Helen also confided that Pauling was not happy with offers that he had received from the Smithsonian, the Library of Congress, Caltech, and many other highly-respected institutions, because they only wanted his papers and not hers, wanted to cherry pick the items that they would keep (Pauling wanted everything kept together), or wanted the papers right away, despite Pauling’s need to retain many of them for his ongoing research.

Hedberg was fully aware that, were OSU to be selected by Pauling as the repository for his papers, the announcement would serve as a major boost in prestige. He also understood that if Pauling’s bitterness against the university were to be assuaged, the conciliation would have to come from the university president. In short order, Hedberg wrote to OSU President James Jensen, stating that “…it seems to me that Pauling’s eminence in science and in world affairs together with his historical association with the State of Oregon and Oregon State University makes this a proper place for these papers.” He further suggested that if “…handled correctly, it might be possible for Oregon State to obtain these papers.”

Pauling’s split with Oregon State College came about as a direct result of actions taken by President August Strand, who led the institution from 1942 to 1961. His successor was James Jensen, who took over shortly after OSC became OSU, and it was under Jensen’s watch that the relationship with Pauling came to be repaired. Spurred by Hedberg’s note, Jensen wrote to Pauling lamenting the rift that had grown between him and the university, assuring him that he remained one of the university’s most beloved alumni, and concluding that

When it comes time to think of a repository for your letters and other documentary matters, I hope you will consider the possibilities of Oregon State University and its repository of important papers which is located within a stone’s throw of where you and Mrs. Pauling met!

Jensen also created a Distinguished Service Award in 1964 and made Pauling the first recipient.

Finally, in 1966, the president extended an invitation to Pauling to speak at the university, which was accepted. In December of that year, he delivered a well-attended convocation lecture titled “Science and the Future of Man” at Gill Coliseum. It was the first talk that he had given on the Oregon State campus since a 1937 lecture on hemoglobin and magnetism, which he had presented at the dedication ceremonies for the Oregon State chapter of the Sigma Xi scientific research honorary.

With the ice finally broken, Pauling began returning to the university more frequently, eventually regaining his old affection for OSU and choosing to make trips to Corvallis whenever he was passing through the area. Pauling also admitted that he was “pleased” by OSU’s request for his papers, telling Jensen that in addition to OSU, he had offers in hand from the Library of Congress, the American Philosophical Society, and the University of Oregon, among others. As he continued to ponder the final home for his materials, he asked that Jensen have the university archivist send him a letter describing OSU’s archival facilities and the plans that it would put in place for the preservation and use of the papers.

In March 1967 Jensen again wrote to Pauling, this time including a draft donation agreement as well as the requested comments on facilities from the university archivist. By July, Pauling had largely been won over and claimed that he felt ready to begin giving his papers to the university. That said, he was as busy as ever and seemed reluctant to actually part with any of his material. His continuing research and trips to Europe, combined with disruptive California wildfires, meant that he never had time for OSU’s archivist to visit him to evaluate and organize the collection.

For whatever reason, Pauling continued the stall tactics for the remainder of Jensen’s tenure as president. In 1972, Hedberg wrote to Jensen’s successor, Robert MacVicar, to loop him in on the conversation. In addition to forwarding copies of past communications between himself, Jensen, and Pauling, Hedberg expressed his point of view that Jensen’s negotiations seemed to have been successful, but hastened to add that a final agreement was never reached. Jensen, sensing Pauling’s hesitation, had eventually stopped asking about the papers for fear of endangering the relationship that he had successfully rehabilitated.

Hedberg encouraged MacVicar to pick up where Jensen had left off in trying to obtain the papers. MacVicar took the suggestion to heart and contacted Pauling, but kept Hedberg in the loop since he knew Pauling so well. Over time, Hedberg was able to mediate communications somewhat, often advising MacVicar on how he thought Pauling might interpret different phrases of a draft letter and predicting how he would respond. Pauling still felt that he was not ready to part with the papers, so MacVicar followed Jensen’s precedent and focused on maintaining a good relationship with Pauling with the occasional gentle reminder about his promise to give his papers to OSU.

Activist Norman Cousins, Portland mayor Bud Clark, Linus Pauling and OSU President John Byrne at a celebration marking Pauling’s donation of his papers to Oregon State University.

Ava Helen passed away in 1981 and the next year Hedberg helped to found the Ava Helen Pauling Lectureship on World Peace at OSU. Meanwhile, in 1984 John Byrne replaced MacVicar as OSU president and, once again, Hedberg forwarded copies of past correspondence and encouraged the new president to continue the effort. Byrne saw that, while his predecessors had succeeded in winning Pauling over, their gentle reminders had done little to motivate Pauling to actually make the donation.

Byrne decided to change tactics by setting up a committee to handle the negotiations, from which emerged a concrete offer to build a Special Collections unit that would house and manage the donated materials. Byrne also agreed to all of Pauling’s requests regarding the treatment of the collection: namely, that Ava Helen’s papers be included in the acquisition, that the collection be kept intact, that the collection be made available for use by any qualified researcher, and that Pauling himself also receive unfettered access should he need to consult any of his old letters or manuscripts. Among these requests, the Ava Helen piece was likely the most significant; with her passing, it became particularly important to Pauling that her papers be treated with the same deference as his own.

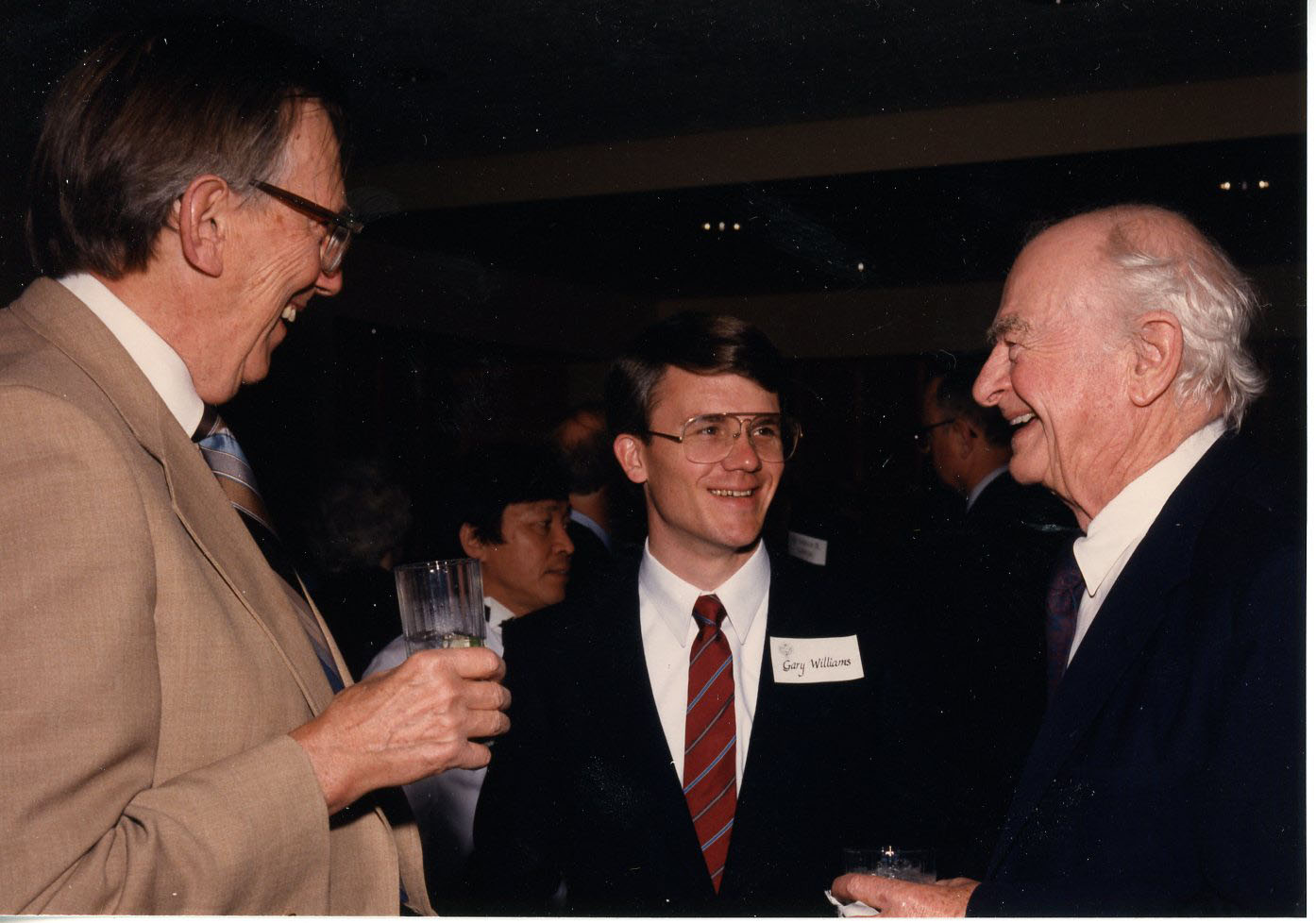

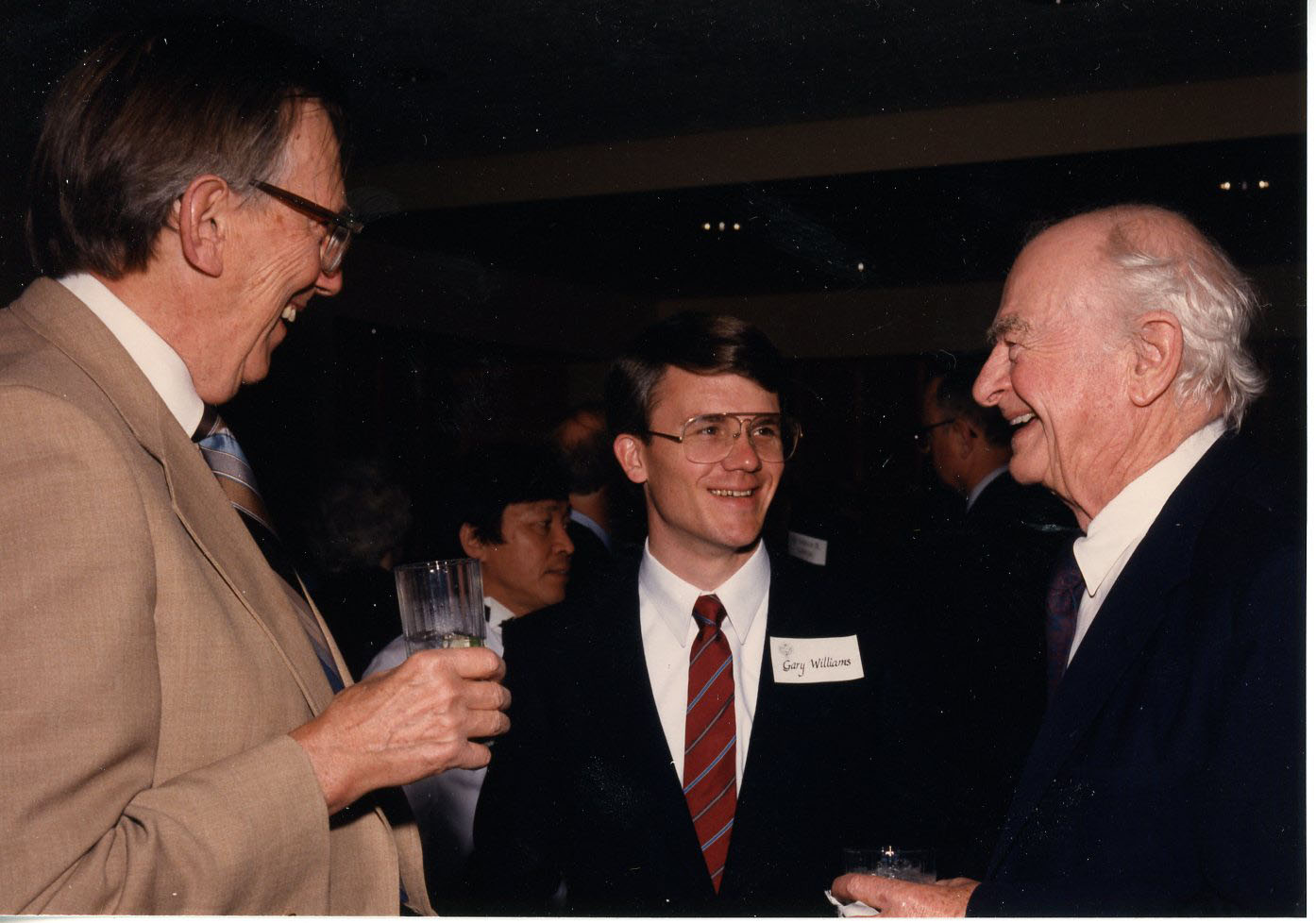

Hedberg and Pauling among others at an event celebrating the donation of the Pauling Papers to Oregon State University, April 1986.

At long last, on April 18, 1986, Pauling formally announced that he would be transferring his papers to the Oregon State University Libraries. The first item that Pauling sent to OSU was the three volume United Nations Bomb Test Petition, an encapsulation of the work for which he received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1963. Other materials were added gradually over the rest of his life, once he had decided that he did not need them for his current research activities. Eventually the university sent a representative to Deer Flat Ranch to see how big the Pauling collection was, and they found that he had over 90 filing cabinets full of materials just at his Big Sur home.

As Pauling made more frequent trips to Corvallis, Hedberg was usually assigned to act as his guide and chaperone. On one reminiscent wander around campus, Pauling pointed out to him the room in present-day Furman Hall where he first met Ava Helen. He also showed Hedberg the house on 15th street where he had lived as a student.

Frequently, the Hedbergs and the Paulings were participants in the same dinner parties, some of which were hosted by Ken and Lise. Pauling was fond of vodka and often favored a drink prior to attending a formal event; Ken always made sure that Pauling’s preferred brand was in the cabinet. Another time, at a dinner party hosted by the Hedbergs, Pauling recognized the wine that they served as being of the same vintage as that served at a similar party the previous year. Hedberg was shocked that, of all the dinner parties and events that Pauling attended, he would remember the wine that had been served at a particular gathering a year prior.

Ken Hedberg, David Shoemaker and Lise Hedberg at a dinner party hosted by OSU President John Byrne, 1991. Linus Pauling was seated across the table from Ken Hedberg.

Though they saw one another with some frequency, Pauling and Hedberg continued to make time to provide updates on their lives through correspondence. Pauling wrote to Hedberg about his own rectal cancer, and Hedberg asked Pauling for advice concerning a friend’s inoperable cancer and for managing Lise’s arthritis. Ken also shared the unhappy news when their mutual colleague, David Shoemaker, died of complications related to kidney disease. Ken likewise expressed his frustrations to Pauling when the National Science Foundation reduced his grant funding in 1992 due to concerns about his age.

Political and social issues also frequently came up in Pauling and Hedberg’s communications, and the two friends tended to share a similar mindset on the issues of the day. Like Pauling, Hedberg was firmly opposed to the use of nuclear weapons and, following a 1961 visit to Hiroshima, wrote that “…I believe world peace could be assured by simply escorting the world’s political leaders through the park and museum.” In a different letter written that same year, Hedberg confided that

Lise and I…were utterly dismayed at the resumption of nuclear testing. Most of us feel that the fallout problem is bad enough, but what really frightens is the return to the mailed fist kind of diplomacy they represent… I’m quite convinced that the world is controlled by people gone mad. My more optimistic friends aren’t so worried – ‘after all, another world war is unthinkable.’ What impresses me over and over, though, is how full of irrational people the world is, how singularly alike in some respects the opinions of such people are, and how easily national attitudes seem to be born of such opinions… Most people seem unable to comprehend that the ancient techniques of enforcing national interests on an international scale will lead only to their destruction. Perhaps a part of this is due, at least on the local scene, to what people imagine death to be like. Corvallis is a religious town, and as one of my physicist friends put it, ‘most people here feel that death is a new experience, rather than what it is – the complete absence of experience for all eternity.’

Hedberg retired from OSU in 1987, a moment that prompted a letter of congratulations from his friend and former mentor. In it, Pauling confessed that “I remember you, Ken, as one of my favorite graduate students in the California Institute of Technology.” Once his retirement festivities were completed, Hedberg penned a note of gratitude in response.

I think this is also the time for me to tell you how much I have appreciated your help and support during my professional career. You’ve written many recommendations on my behalf without which my life would have been totally different. It would have been nearly impossible to build my laboratory without help from the Research Corp., the Sloan Foundation, and others, to which you sent words on my behalf. Perhaps you are even responsible for Lise’s entering my life – without my Guggenheim to Norway we would never have met! And lastly, you are surely responsible for my accepting a position here at Oregon State. You encouraged me to accept the job, and apart from problems at the start, Lise and I have been very happy here.

Filed under: Colleagues of Pauling | Tagged: Ava Helen Pauling, James Jensen, John Byrne, Ken Hedberg, Linus Pauling, Oregon State University | 1 Comment »

![1963i.037-[3967]-300dpi-550w](https://paulingblog.files.wordpress.com/2017/07/1963i-037-3967-300dpi-550w.jpg)

![1964i.035-[1329]-300dpi-550w](https://paulingblog.files.wordpress.com/2017/07/1964i-035-1329-300dpi-550w.jpg)

![1970i.013-[1397]-300dpi-550w](https://paulingblog.files.wordpress.com/2017/07/1970i-013-1397-300dpi-550w.jpg)

![1971i.012-[2519]-300dpi-550w](https://paulingblog.files.wordpress.com/2017/07/1971i-012-2519-300dpi-550w.jpg)

![1971i.024-[3413]-300dpi-550w](https://paulingblog.files.wordpress.com/2017/07/1971i-024-3413-300dpi-550w.jpg)

![1972i.016-[2529]-300dpi-550w](https://paulingblog.files.wordpress.com/2017/07/1972i-016-2529-300dpi-550w.jpg)

![1975i.097-[2171]-300dpi-550w](https://paulingblog.files.wordpress.com/2017/07/1975i-097-2171-300dpi-550w.jpg)

![1977i.014-[1887]-300dpi-550w](https://paulingblog.files.wordpress.com/2017/07/1977i-014-1887-300dpi-550w.jpg)

![1977i.033-[3184]-300dpi-550w](https://paulingblog.files.wordpress.com/2017/07/1977i-033-3184-300dpi-550w.jpg)

![1977i.044-[1930]-300dpi-550w](https://paulingblog.files.wordpress.com/2017/07/1977i-044-1930-300dpi-550w.jpg)

![1978i.054-[2654]-300dpi-550w](https://paulingblog.files.wordpress.com/2017/07/1978i-054-2654-300dpi-550w.jpg)

![1931i.040-[3937]-300dpi-550w](https://paulingblog.files.wordpress.com/2017/07/1931i-040-3937-300dpi-550w.jpg)

![1933i.009-[554]-300dpi-550w](https://paulingblog.files.wordpress.com/2017/07/1933i-009-554-300dpi-550w.jpg)

![1934i.005-[548]-300dpi-550w](https://paulingblog.files.wordpress.com/2017/07/1934i-005-548-300dpi-550w.jpg)

![1935i.012-[1564]-300dpi-550w](https://paulingblog.files.wordpress.com/2017/07/1935i-012-1564-300dpi-550w.jpg)

![1938i.011-[933]-300dpi-550w](https://paulingblog.files.wordpress.com/2017/07/1938i-011-933-300dpi-550w.jpg)

![1939i.005-[920]-300dpi-550w](https://paulingblog.files.wordpress.com/2017/07/1939i-005-920-300dpi-550w.jpg)

![1940i.025-[683]-300dpi-550w](https://paulingblog.files.wordpress.com/2017/07/1940i-025-683-300dpi-550w.jpg)

![1947i.022-[2046]-300dpi-550w](https://paulingblog.files.wordpress.com/2017/07/1947i-022-2046-300dpi-550w.jpg)

![1953i.025-[2413]-300dpi-550w](https://paulingblog.files.wordpress.com/2017/07/1953i-025-2413-300dpi-550w.jpg)

![1954i.038-[1447]-300dpi-550w](https://paulingblog.files.wordpress.com/2017/07/1954i-038-1447-300dpi-550w.jpg)

![1954i.046-[1645]-300dpi-550w](https://paulingblog.files.wordpress.com/2017/07/1954i-046-1645-300dpi-550w.jpg)

![1902i.002-[36]-300dpi-900w](https://paulingblog.files.wordpress.com/2017/07/1902i-002-36-300dpi-900w.jpg)

![1906i.002-[16]-300dpi-900w](https://paulingblog.files.wordpress.com/2017/07/1906i-002-16-300dpi-900w.jpg)

![1908i.1-[33]-300dpi-900w](https://paulingblog.files.wordpress.com/2017/07/1908i-1-33-300dpi-900w.jpg)

![1917i.003-[123]-300dpi-900w](https://paulingblog.files.wordpress.com/2017/07/1917i-003-123-300dpi-900w.jpg)

![1918i.029-[21]-300dpi-900w](https://paulingblog.files.wordpress.com/2017/07/1918i-029-21-300dpi-900w.jpg)

![1918i.033-[3694]-300dpi-900w](https://paulingblog.files.wordpress.com/2017/07/1918i-033-3694-300dpi-900w.jpg)

![1920i.027-[62]-300dpi](https://paulingblog.files.wordpress.com/2017/07/1920i-027-62-300dpi.jpg)

![1920i.052-[27]-300dpi-900w](https://paulingblog.files.wordpress.com/2017/07/1920i-052-27-300dpi-900w.jpg)

![1922i.014-[1002]-300dpi-900w](https://paulingblog.files.wordpress.com/2017/07/1922i-014-1002-300dpi-900w.jpg)

![1924i.027-[330]-300dpi-900w](https://paulingblog.files.wordpress.com/2017/07/1924i-027-330-300dpi-900w.jpg)

![1925i.002-[421]-300dpi-900w](https://paulingblog.files.wordpress.com/2017/07/1925i-002-421-300dpi-900w.jpg)

![1925i.013-[823]-300dpi-900w](https://paulingblog.files.wordpress.com/2017/07/1925i-013-823-300dpi-900w.jpg)

![1926i.062-[3568]-300dpi-900w](https://paulingblog.files.wordpress.com/2017/07/1926i-062-3568-300dpi-900w.jpg)