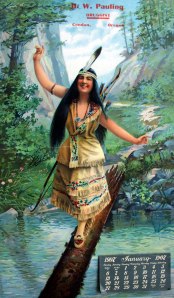

[Ed. Note: The Oregon State University Libraries Special Collections & Archives Research Center (SCARC) is, of course, home to the Ava Helen and Linus Pauling Papers, a collection of some 4,400 linear feet held in 2,230 archival boxes. Also included among the 1,100 collections held in SCARC is the Mervyn Stephenson Collection, which consists of eight file folders. Stephenson was Linus Pauling’s older cousin and was an important early influence in Pauling’s life. We spend a lot of time sifting through the Pauling Papers as we prepare these posts, but we thought it might be fun to engage with MSS Stephenson for a short while and learn a bit more about a man who, in some respects, served as a kind of surrogate big brother for Linus Pauling.]

Part 1 of 2

If he’s lucky, every young boy has his partner when he plays ‘Cowboys and Indians,’ or when he roams the streets getting into mischief. For Linus Pauling, his cohort in crime was his older cousin, Philip Mervyn Stephenson, also referred to as Merv but who also liked to be called Steve. He was born on March 23, 1898 in Condon, Oregon to a Condon native, Goldie Victoria Darling Stephenson, who married an English immigrant, Philip Herbert Stephenson.

Mervyn was about three years older than Linus, but when they were young school boys, the gap made no difference. The Paulings lived in Condon, off and on, until they moved to Portland for good when Linus was eight years old, and it was in Condon that Pauling and Stephenson spent the most time together. As they wandered the town together and explored its hills and gullies, they hunted rabbits, swam in streams, collected arrowheads and, in the winter, took sleigh rides. In later years, Pauling also recalled watching with his cousin as the area’s wheat was being harvested and bringing water to the farmhands.

Sometimes Mervyn’s father asked him to mind the store that he owned. Stephenson and Pauling looked forward to these occasions because these were times where they could sneak sweet treats and other good things to eat. Being left alone to watch the store also led to a few hilarious run-ins. One day the chewing tobacco was left out. The boys decided to try a small piece, probably swallowed a bit, and both got sick. Needless to say, neither of the boys’ fathers were pleased.

Another time, Pauling was asked by his father to watch the family pharmacy. Stephenson, of course, joined and the two decided to try the port wine—it was used for several prescriptions that Herman Pauling wrote. The boys tried a bit of wine, soon became drowsy, and fell asleep in the back of the store. The two got in trouble, once again, and that was the last of their major stunts. By 1909, after the Paulings moved to Portland, time spent with Mervyn never held the same childhood aura or imagination.

The Stephensons bought a family car in 1912 and, at the age of 14, young Mervyn immediately learned to drive. People in town called him a fast driver, and his father had only to call the local store or neighbor to see where his son had gone, because Stephenson would have most likely zipped by in the new car. Stephenson would also frequently hike down a nearby canyon with other kids from Condon and was a big fan of the regional county fairs. He was an adventurous young man and went on numerous excursions, including following local legends in search of a secret lake in the woods.

As he grew up, Mervyn’s parents thought him to be too thin and “understrength” for his own good. To combat this, they would send him, sometimes for a month at a time, to Charles and Nell Underwood’s house, where they would feed him well and work him hard in hopes that he might gain weight and muscle. It was here that Stephenson collected many arrowheads for his collection.

Mervyn was also becoming an upstanding citizen. He was, for one, the lead organizer of the athletic boys club of Condon until he left for college. More importantly, in 1912, (the same year that the family bought their car) he was marked as a town hero for being the first on the scene of a fire in a hotel. Mervyn had heard the siren in the middle of the night, rushed over to the fire station, and then hurried to the hotel to help. The town awarded him with a prize of one dollar for acting promptly and courageously.

Around the time of Mervyn’s graduation from Condon High School in 1915, Professor Gordon Skelton of Oregon Agricultural College (OAC) came to town to recruit students. He met Stephenson and they talked about what he might want to study should he attend OAC. After their conversation, Skelton had convinced Stephenson to give Corvallis a try and to major to civil engineering. Mervyn visited the Paulings on his way to OAC, and he talked with young Linus, at the time fourteen years old, about his plans to study highway engineering. The two also discussed other programs available at OAC and from this conversation Pauling learned that the college offered chemical engineering, which he believed to be the profession that chemists pursued.

Mervyn worked very hard as a freshman. Room and board ran to about twenty dollars a month, and he found a campus job that paid twenty cents an hour. He made it through his first year working full time with a full class schedule. During summer break, he was hired by the county to work on road construction, and that helped to make ends meet.

Stephenson concentrated on his ROTC training during in his second year at OAC; he moved up as a cadet captain and continued to progress forward. This year was also exceptionally tough because, midway through, his parents were divorced. His sister and mother then moved to Portland. That summer he worked on his first bridge, and as the break came to a close he was offered a job to continue to work on bridges. In order to take the job he would have to take a year off college. He would be paid a fair sum, but following the advice of his father, he decided to finish school and then pursue a career.

The United States was in the middle of World War I through Stephenson’s third year at college. As such, Stephenson transferred from the ROTC to the SATC (Students Army Training Corps) to receive training for combat, if needed. This same year, Linus Pauling, though only sixteen years old, began his studies at OAC. The only reason why Pauling’s mother, Belle, allowed him to go to college at such a young age was because she knew that Mervyn would be there for him.

Little did she know that no college junior wanted to spend his time watching over a sixteen-year-old freshman. According to Pauling’s recollection, soon after Belle left to return to Portland, Stephenson gave Pauling some advice about being in college, and then left him to fend for himself in the boarding house where they were supposed to be living together. Pauling did not stay past the first year in the boarding house, due to the cost of rent, and he did not see much of his cousin while in college.

In Stephenson’s handwritten memoir, titled P.M. Stephenson’s Life Stories, he recalled living with Pauling the entire first year and never mentions leaving Pauling behind. On the contrary, the manuscript focuses mostly on Pauling’s brilliance, describing a young man who would finish assignments quickly and then immediately find something more to teach himself. We learn from the memoir that one of the scholarly hobbies that Pauling picked up as an undergrad was teaching himself Greek. Stephenson was impressed, but being a more veteran college student, he spent ample time studying and his free moments socializing. Perhaps it was these diverging interests that led the two cousins to spend so little time together.

The two young men were very much together in the summer of 1918 when they left for San Francisco for intensive officer training at the Presidio military base. Stephenson recalled Pauling as having been a strong supporter of the war effort while at the camp. With the completion of his officer training, Stephenson was promoted to the rank of cadet major. He was then one of ten men at OAC to receive recommendation for commission as second lieutenant in the Officer’s Reserve Corps. That summer the cousins also worked together when they stayed in Tillamook, on the Oregon coast, with Stephenson’s mother. The two worked in a shipyard for the summer, building wooden-hulled freighters and taking small holidays in their off hours to go with Stephenson’s mother and sister to the resort town of Bayocean.

Stephenson’s senior year looked as if it would begin with a move overseas to serve in the war. Mervyn had received his second lieutenant commission and was notified that he would report to Fortress Monroe, Virginia, but his orders were never received because the war ended on November 11 of that year. He finished his senior year in due course, graduating from OAC’s College of Engineering, and was granted membership in the Zeta chapter of the Sigma Tau engineering honorary society. Mervyn and Linus then parted ways as Pauling continued his studies and Stephenson moved forward in his career as a bridge builder all across Oregon.

Filed under: Colleagues of Pauling, Pauling and Oregon | Tagged: Condon, Corvallis, Linus Pauling, Mervyn Stephenson, Oregon Agricultural College, ROTC, Tillamook | Leave a comment »