[Part 2 of 2]

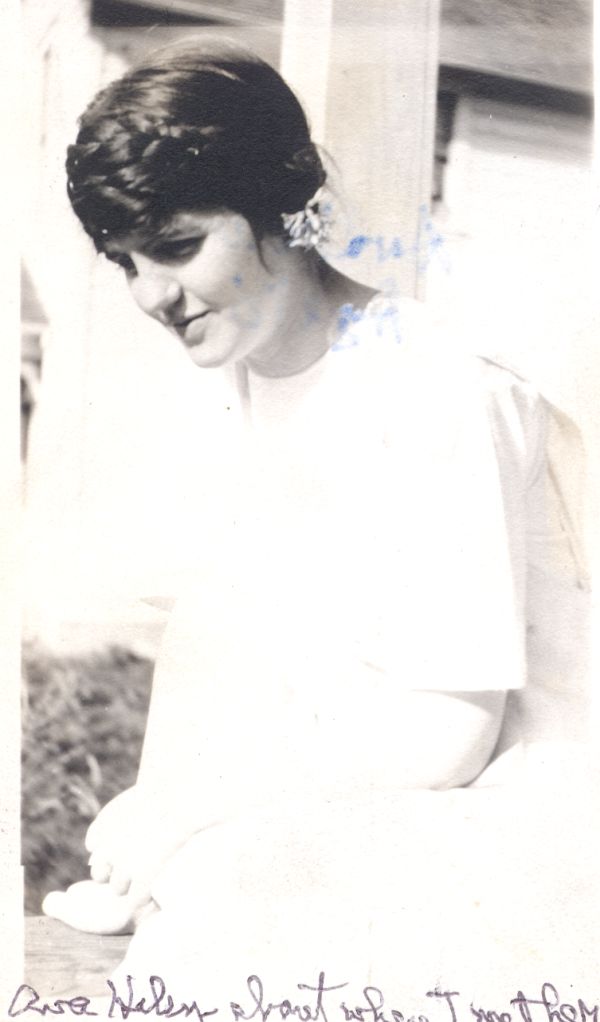

Ava Helen Miller entered Oregon Agriculture College, now Oregon State University, as a freshman in the fall of 1921. During that first year, she met Linus Pauling, and shortly thereafter the two fell in love and became engaged. This chance meeting derailed her plans to continue her formal education, and after five terms at OAC, she left school to start her life with Pauling. But even though she spent less than two academic years in Corvallis, Ava Helen made the most of her experience.

The tenth of twelve children, Ava Helen was born in 1903 in Beavercreek, Oregon, an unincorporated area southwest of Portland. When the time came to begin considering colleges, OAC proved a natural choice because, by 1921, three of her siblings were already attending the school. These siblings were her brother Milton, a senior majoring in agriculture; another brother Clay, a junior also studying agriculture; and sister Mary, a senior in home economics. Like Mary, Ava Helen entered OAC as a home economics major. And instead of living in a women’s dormitory like most first-year students, Ava Helen lived with her siblings in a Corvallis rental home that her mother Nora also resided in.

Though college was not an ordinary expectation for women of the era, a higher education seemed to be in the cards for Ava Helen. She had always excelled as a student, graduating from Salem High School in three years as the class president. Buoyed by her past successes, Ava Helen enrolled in a wide variety of courses during her OAC tenure, including Spanish and French, languages for which she showed a particular aptitude.

Generally speaking, her performance in college improved as she became more settled. During her first term, she received mostly Bs with a C in general chemistry and an A in English composition. Interestingly, during her second quarter, Ava Helen received her only F, which was also in English composition. That winter term was clearly challenging with respect to academics, as her grades were somewhat worse than was typical for the rest of her OAC time. (Coincidentally or not, this was also the term in which she met her future husband.) But later, her grades improved. In her last quarter, she took Child Care and received an A, perhaps a foreshadowing of her future responsibilities as a mother of four.

Chemistry was always one of her best subjects, and instructors besides the young Pauling took note of her chemistry aptitude. One of them, an organic chemistry instructor named Mr. Quigly, remarked that she was among his best students. Despite this aptitude, Ava Helen notably received a B in general chemistry during the winter term of her first year, a grade that she felt was lower than she deserved. This belief was accurate, but because the instructor for the course was her soon-to-be husband, the instructor – “boy professor” Linus Pauling – deliberately lowered her grade from an A to a B, in an effort to obfuscate any potential impropriety. This decision remained a source of good-natured ribbing between the couple for years to come.

Ava Helen pursued interests outside of academics during her stint in Corvallis. She joined the school’s drama club, known as the Mask and Dagger, during her first year. The club produced several plays including larger productions like Shakespeare’s “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” and “Clarence,” a modern “light comedy” by Booth Tarkington. Near the middle of the year, Ava Helen hit the stage in a one-act offering titled “Pierro by the Light of the Moon” by Virginia Church; Ms. Miller was cast as Columbine, the second lead.

During her second year at OAC, Ava Helen also served as secretary of the Lyceum Club, which consisted of “musicians, readers, and lecturers.” The club focused on coordinating cultural events for the local community and, during Ava Helen’s year, hosted several prominent artists and musicians, including the Flonzaley String Quartet.

A discussion of Ava Helen’s time at OAC would be remiss if it did not include mention of her romance with Linus Pauling. During the winter term of her first year, she was enrolled in a general chemistry course that was mandatory for all home economics majors. Pauling, himself a fifth-year senior at OAC, was assigned to teach the class, though he was only a few years older than the students that he was asked to teach. Shortly after their first encounter in January 1922, Ava Helen and Linus hit it off, and by the end of the school year they were engaged.

In the summer of 1922, Pauling left Oregon to begin his graduate studies at Caltech while Ava Helen continued her schooling, starting her second year at OAC. The initial plan was for Ava Helen to stay at OAC and complete her degree while Pauling worked on his Ph.D, and the pair wrote to each other nearly every day, and saw one another on breaks. But the waiting and separation proved too much, and by the end of the second quarter of her second year, in March 1923, Ava Helen dropped out of school in order to plan her wedding. In June 1923, the couple married and Ava Helen moved to Pasadena to begin a new life.

Filed under: Ava Helen Pauling, Pauling and Oregon | Tagged: Ava Helen Pauling, Oregon Agricultural College | Leave a comment »