[Post 8 of 8 in our series examining Linus Pauling’s relationship with his long-time publishing house, W.H. Freeman & Co.]

In the 1970s and 1980s, well after Bill Freeman’s departure from the company that he started, Linus Pauling published a number of other books through Freeman and Co., including two big sellers, Vitamin C and the Common Cold, and How to Feel Better and Live Longer, as well as Orthomolecular Psychiatry, which was more of a niche volume. But as the staff at Freeman and Co. evolved, Pauling began to experience trouble communicating.

Over time, Pauling also felt his editorial contributions were being restricted. Notably, when Basic Physical Chemistry for the Life Sciences was published as part of his series, Pauling had no hand in editing it. Once the book had gone to the printers, Pauling sent a letter to Freeman & Co. president Stanley Schaefer stating his belief that the text should not have been released in this manner. No text, he felt, should be published in his series if he was not really and truly the editor.

Schaefer replied that he had no intention of impinging upon Pauling’s authority over the series, but did express his feeling that Pauling’s fame worked against the company at times. In addition, Pauling’s manuscript comments were often very blunt, and while it is unclear how many authors were given the opportunity to read Pauling’s assessments directly, those who did were often upset by comments that they felt were unfair.

One author in particular, an R. Nelson, wrote several pages to Schaefer defending his stylistic choices after the company had rejected his manuscript. Pauling, for one, had criticized his informal tone, but Nelson felt that the approach made the book more appealing to younger generations of scientists. Nelson then attacked the company’s decision to retain Pauling as an editor for the chemistry series, writing

The problem really arises because the chemistry editor is the author of the first text and is a man of strong convictions (as well as great prominence). I believe that this situation puts a potential author (one with no prominence) in an untenable position.

Schaefer was moved by this comment in particular and asked Pauling to reconsider the manuscript with the understanding that some minor errors would be corrected. In so doing, Schaefer also sided with Nelson’s point of view in suggesting that Pauling’s take was based largely on differences in style. In this instance, Pauling was flexible and reconsidered.

In 1970, to help with the problem that Nelson had raised, Schaefer hired Pauling’s friend, colleague and former student, Harden McConnell, to serve as a co-editor for the chemistry series. McConnell was someone whom Pauling respected and who also tended to be rather more gentle in his critique, and the arrangement worked out well. The collaboration likewise helped to spread the editorial responsibilities such that Pauling could dedicate more time to other projects.

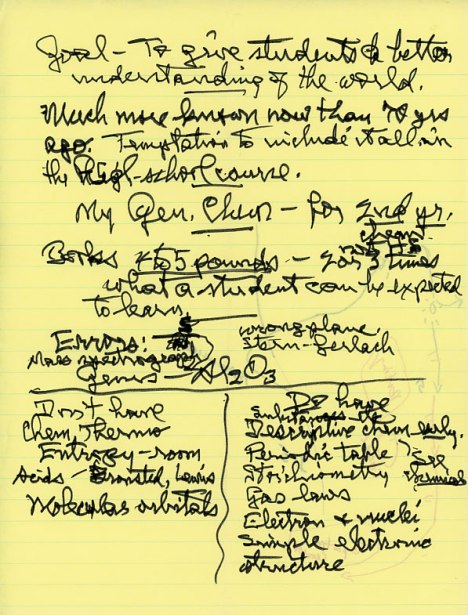

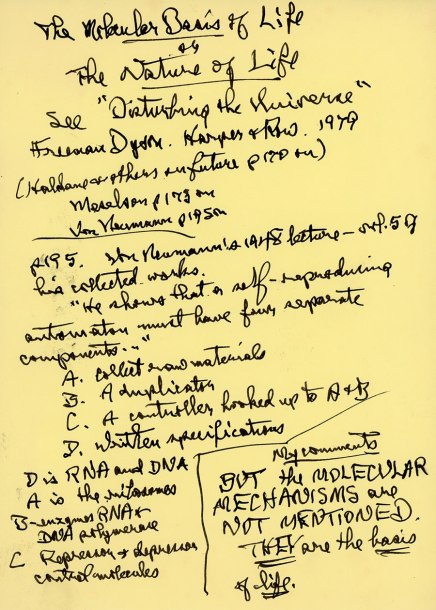

Pauling’s notes for his memoir.

The situation had changed substantially by 1979 when Richard Warrington, the latest president of the company, suggested that Pauling terminate his editing contract. Though stressing that Pauling’s “association with the company as an author and adviser in the early years was very important to the success that followed,” Warrington also pointed out that Pauling was no longer teaching. As such, Warrington worried that Pauling’s interests and priorities had changed significantly. He also felt that the Freeman company hadn’t been as effective at bringing in successful chemistry texts in recent years. Pauling felt similarly, but also pointed out that the flow of manuscripts from the company had slowed considerably.

As the company continued to experience leadership changes throughout the 1980s and 1990s, Pauling’s relationship with Freeman as an author also began to deteriorate. Notably, at the same time that Warrington had asked him to terminate his editing contract, Pauling discovered that the company had allowed his landmark General Chemistry to go out of print. Another milestone came about a year later when Neil Patterson assumed the role of president and moved the company to New York to be closer to Scientific American, with which Freeman and Co. now shared a CEO. Pauling had long enjoyed having a publisher based on the West Coast and was disappointed with the move.

In 1991, a correspondent named Jonathan Paul Von Neumann wrote a letter to Pauling expressing his disappointment that Freeman and Co. hadn’t shown any interest when he approached them about translating How to Feel Better and Live Longer into other languages. Pauling wrote back, sharing Von Neumann’s concern and confiding his belief that publishing companies often mishandled their authors.

In 1992, Pauling’s relationship with Freeman and Co. all but came to a close when the publisher rejected two of his proposed manuscripts. One was a freshman text that he planned to write with his youngest son, Crellin. Perhaps more disappointing was the firm’s lack of interest in Pauling’s second suggestion, a memoir that he was to title The Nature of Life — Including My Life.

W.H. Freeman and Company was eventually reabsorbed into its parent company. Now an imprint under Macmillan Learning, the group continues to publish successful science textbooks and provide other educational resources.

Perhaps more than anything else, William Hazen Freeman was a man who created a network of scientists who came together to write, edit, and circulate textbooks geared at improving science education in university classroom. In pursuing this ambition, he harnessed the brilliance of scientists who were top-notch in their fields and commissioned them as editors or writers (or, in the case of Pauling, as both) to disseminate knowledge and advance disciplines. As a result, W.H. Freeman & Co. was, in its prime, a hub for collaboration and communication between scientists and other creative thinkers. It is likely that no other corporation played as profound a role in Pauling’s story than did his long-time publisher.

Filed under: Colleagues of Pauling | Tagged: Linus Pauling, Stanley Schaefer, W. H. Freeman | Leave a comment »