[Editors Note: The Oregon State University Libraries Special Collections is very pleased to announce that it will soon serve as home to the Roger Hayward Papers. Hayward was a hugely-talented artist who, among many other projects, collaborated with Linus Pauling as illustrator to a number of Pauling’s books, most notably The Architecture of Molecules (1964). This blog post represents the first installment of a four-part biographical series on Hayward that The PaulingBlog will be running over the next two weeks. The text of these posts has been compiled by Dr. J.R. Kramer, Miriam Kramer (Hayward’s niece) and John Benjamin (Hayward’s cousin). Questions about Hayward may be addressed to the Kramers via email at jkramer2[at]cogeco.ca High-resolution versions of all images presented in the Hayward biographical sketch may be accessed by clicking on the thumbnails presented within the texts.]

Perhaps it is a bit providential that Roger Hayward and Linus Pauling met and then later worked together to advance the understanding of molecular structure. This association between a chemist and an architect-artist (Pauling called him a scientist) perhaps reached an apex in the publication of the acclaimed Architecture of Molecules. Roger Hayward, however, was more than an illustrator, and this, in brief, is his story.

Beginning Years:

Roger Hayward at 8 months.

Roger Hayward was born in Keene, New Hampshire in 1899. Mother’s diary says, – “2.15 (AM) the baby – a son – was born, named Roger. – – – Baby weighed 8 lbs: had lots of hair: cried lustily even raising his head and kicking before cord was cut.”

Roger’s mother, Ina Phelps Hayward, was an artist and the daughter of a well-known New England artist, William Preston Phelps. Roger was given a sketch book at age 7 and began drawing. In a letter in 1950 he wrote, “Mother was an artist’s daughter. I was expected to draw just as I was expected to eat or talk or anything else, and I wasn’t praised for the results.” Roger’s father, Robert, was a well-known Keene businessman who also designed, built and repaired time pieces and other small mechanical devices. Roger entered the Massachusetts Institute of Technology with the idea of studying architecture: “I decided on architecture because I hoped it would provide a balanced diet of aesthetics and mechanico-science.” He was eighteen years old and, certainly, his senses of perspective and composition were well-developed. As a student in architecture at MIT, he had ample opportunity to practice his draftsmanship and the application of color — albeit in a restricted, technical fashion.

This sketch is an example of one of Hayward's student projects, an opera house foyer.

He also had fun at Tech. One noteworthy example is his “Mask of Tragedy” drawing. From the Boston Evening Transcript for Sat. May 28, 1921:

For outlet to the exuberance of talent which refuses to confine itself to perspectives and formal ‘projects,’ the students in the Department of Architecture at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology hold an exhibition of their own each year, at which they caricature their instructors, give rein to their fancy and hang on the walls of a room in the Rogers Building whatever of their work best pleases them. This year the imagination and skill of one of the students, Roger Hayward, evolved a Mask of Tragedy, which on close inspection is found to be interpreted in terms of figures of the modern stage.

The Mask of Tragedy.

Upon graduation in 1922, he received a number of honors from MIT: a prize from the Boston Society of Architects, two Chandler Medals (for projects completed while a student) and the Rotch Prize, which carried with it an award of $200.

He then married Elizabeth (Betty) Hatfield, and they spent the prize money at Cape Cod on their honeymoon, reading and sketching. Betty had grown up on a farm in Iowa. She was orphaned at an early age, but went on to high school and to Grinnell College. Afterward she taught English and beginning Latin for one year and then went to Radcliffe College where, as a graduate student in English, she met Roger. Roger and Betty then settled down in Boston, where Roger worked for various architectural firms.

Mostly Art:

Naval barracks oil painting.

The earliest known example of an oil painting from Roger is a sketch of the barracks where he was stationed as a Naval Reservist immediately after his high school graduation. Roger volunteered, as did so many others, for the “Great War”, but was spared the danger of combat by the Armistice of 1918.

Of course, Roger indulged in his share of “high jinks” and other student activities to which his artistic talents could be lent. The “S. S. P. Co.” in Figure 5 refers to S. S. Pierce Company, a high class Boston purveyor of fine foods. “Technique” is the MIT yearbook. One presumes from the golden color of the bottle in Roger’s hand that beer was among the goodies provided.

Hijinks watercolor.

Roger graduated from “Tech” in 1922, a year late due to illness, likely the one which occasioned the “care package” in the hijinks piece. Roger took a position at Bellows and Aldrich, later Wm. T. Aldrich, a Boston architectural firm. In 1925, he moved to Cram and Ferguson, a well-known Boston architectural firm specializing in gothic design. Cram and Ferguson were working on the N.Y. cathedral, St. John the Divine, and Roger did a number of architectural designs and renderings of the north face.

Pencil rendering of proposed North Face of St. John the Divine, NYC. (Pencil Points, May 1926).

Pencil rendering of for proposed Presbyterian cathedral, Washington, DC. (Architectural Design. March, 1929 p. 30).

He also did similar artistic renderings for the two WWI military cemeteries in France at Aisne-Marne and Oise-Marne (see NY Times, July 17, 1927, article by Henry Miller) for which Cram had commissions. Ralph Cram sent Roger and Betty to Europe in 1926 to examine and sketch many classical buildings and to see “real Gothic structure”. During the trip, Roger filled sketchbooks with his carefully-rendered drawings and color studies. This “inspection trip” would be valuable in developing ideas for many of the later California architectural projects. Although his trip was confined to Italy, France and England, one of the sketch books opens with a watercolor drawing of the Hagia Sophia in “Constantinople”.

Hagia Sophia watercolor.

Roger’s water colors were first exposed to the public eye in early 1928 when some two-dozen of his paintings were exhibited at the Grace Horne Gallery in Boston. They were received with restrained polite comment. One critic wrote, “His water colors, indicative of due appreciation of nature, are sincere endeavors to record various aspects, but have the restraint of one who has not yet attained to freedom in the use of the brush.” This was, one supposes, a stilted way of saying he was too meticulous. One also suspects that it was not common for any new artist to gain instant approval, especially one whose training was technical rather than artistic. The writer did note, however, that “One has to begin somewhere, however, and the present exhibition has a promise in its best works that should encourage toward further showings.”

In May of that same year Roger entered more paintings at the Business Men’s Art Club exhibit and was greeted in the Boston Herald with the heading, “Hayward Group Notable.” The writer continued,

Mr. Hayward, long of limb and youthful of feature, doesn’t even bother to avail himself of studio patter in discussing his watercolors. Smilingly he admits that his early efforts got him only a ‘kick in the pants’ from connoisseurs. His most recent paintings, however, are among the most effective in the show. ‘Yes, sir,’ chuckled Mr. Hayward boyishly, ‘I seem to be going like a house afire.’

Another viewer wrote, “There are several nudes, wonderfully painted by this young man whose business acumen must, or should be, very low; for certainly no one who can paint as he does, can have the remotest corner in his brains for business. All this according to the accepted rule y’ know.”

Watercolor perspective of nude (Image courtesy of J. Benjamin).

Lastly Haydon Jones, artist and critic in the Boston Herald, writing about “Business Men and Art” noted “Two or three landscapes, also in water color by the same genius [Hayward] remind one of John Singer Sargent. All they need is his signature, and they would sell for a thousand instead of fifteen dollars.”

Significant progress in a mere three months! Or perhaps the Boston art establishment was through with “hazing” Roger and ready to acknowledge his obvious talent. In June several of Roger’s works in the Boston Art Club exhibition drew more praise saying that he “has come forward fast since his debut at Miss Horne’s gallery earlier this season.”

The following February, 1929, Roger again showed several dozen works at Grace Horne’s gallery, concentrating on paintings made from a trip to Arizona. In a year Roger had become a mainstay of the Boston art scene and was worthy of his first one man show. His works were anticipated and analyzed carefully, “He does not follow the easier path, but attempts effects that are difficult. There are dark recesses in the wood, snow enveloped in cool shadows, mountains enveloped in hazy clouds active waters on rocky paths.” One, of a forest fire and clearly from his imagination, was singled out for praise as was a study, “of the reclining figure of a young woman, seen in foreshortened perspective. A most difficult technical feat, the artist has accomplished the little study with dash and vigor.”

Black and white photocopies of two Western watercolor scenes.

The oils that Roger submitted, however, were not greeted with such enthusiasm. “Unfortunately, what Mr. Hayward undoubtedly possesses in the handling of wash, he lacks in oil, if we may judge by the nine works in that medium now shown.” Apparently one had to pay one’s dues for each medium placed before the Boston critics. Articles continued in the Boston papers through March and April. “…the youthful architect emerges into the arena of painters with few, if any, who have arrived as he has through the roundabout road of pursuing painting as a mere avocation.”

In the meantime he was also making an impression in his new home, Los Angeles, at an exhibit of the California Water Color Society, “Roger Hayward, here from Boston, shows some of his vigorous water colors of the desert and the oil fields, his reactions to new scenes.” Now he was a bi-coastal artist, continuing his exhibits in Boston where his paintings of the West were also popular. “Roger Hayward, now resident in Los Angeles, has continued to advance in technique while he explores regions new to him for effective subjects”.

Roger’s artistic excellence was evident. In 1931 a California observer noted of his works,

The line, ‘A good picture is worth a thousand words,’ is proven in the work of Roger Hayward, ten of whose paintings are on exhibit. Hayward’s water-colors are realistic rather than impressionistic, and the spectator, in viewing the landscapes, is almost sure to be reminded of a place sometimes visited in that scene of the desert, the Grand Canyon, and the mountain streams are all portrayed in attractive style. Genuine perspective is present in the especially colorful California desert paintings.

His somewhat flamboyant appearance was also helping make him memorable. Columnist Arthur Millier, in the L.A. Times noted,

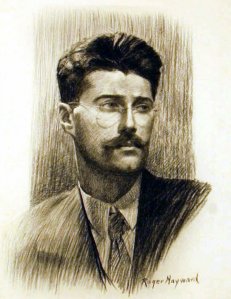

Roger Hayward, water colorist. Gallerygoers would doubtless so describe the author of those brilliant aquarelles of trees, mountains, waves and other subjects seen here during the last three years. They are a small part of his accomplishments. This amazing young man is first an architectural designer whose talent keeps him very busy. In his spare moments he makes the large water colors from memory. He never draws on the spot. But he also makes and operates carefully built puppets, makes original jewelry, designs and carves furniture, and in his spare time raises the most luxuriant mustache in the West. He is 33, looks like Groucho Marx and comes from Boston…

Roger "Groucho Marx" Hayward.

And so on. In Roger’s lifetime, he created over 300 art works, mostly watercolors, and some sculpture and jewelry. He also had time to obtain 10 patents. He sold about 20% of his paintings and gave a few away (one a swap for tutorials in atomic theory from R.M Langer at Caltech). The location of the rest of the paintings are mostly unknown. The above is but an indication of his art accomplishments.

For more on Roger Hayward, click here.

Filed under: Colleagues of Pauling, Featured Documents, Roger Hayward, Site and Department News | Tagged: featured document, Roger Hayward | 10 Comments »