[Tracing Linus Pauling’s association with the W.H. Freeman & Co. publishing house. This is post 7 of 8.]

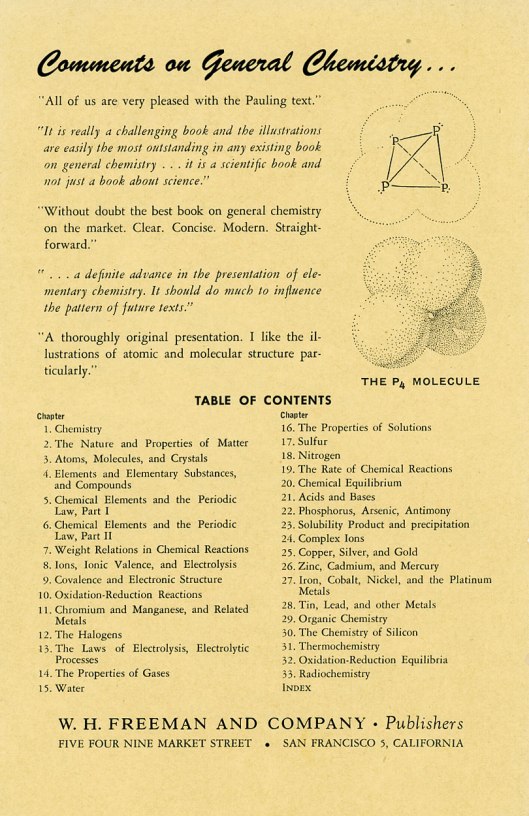

In the years immediately following Bill Freeman’s departure from the company that he founded, Stanley Schaefer ran W.H. Freeman & Co. quite smoothly. In 1969, Bill Kaufman took over as president with Schaefer staying on as chairman, and Kaufman also did well. Notably, he played a key role in the release of revised editions of Linus Pauling’s General Chemistry and College Chemistry, and by the end of his first year in charge, Schaefer was able to report that the company had grown. As the onset of the 1970s loomed, Freeman & Co. had published fourteen new books and added seventy-two titles to its Scientific American offprint series. The outlook for the next fiscal year seemed bright.

The connection with Scientific American was especially important, as the company had formally merged with the publication in 1964. Of this change Schaefer remarked,

Now united are the forces of two successful, non-competitive publishers who have outstanding reputations for high standards and excellence in scientific publishing. Each is making distinctive contributions to the new alliance. I mention, for example, the significant new source of authors for Freeman books that is now available to us.

Illustrator Roger Hayward, who had spent years working for both Freeman and Scientific American, expressed surprise at this news, but congratulated both parties and noted that the transition seemed to him a “happy circumstance.”

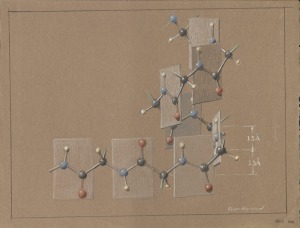

That same year, Pauling and Hayward began collaborating on The Architecture of Molecules, originally titled Molecular Architecture but renamed by Pauling just prior to its release. A stunning and unique collision of science and art, the book was successful right away and continued to do well for years afterward. Both collaborators received 15% royalties for the first 10,000 copies sold in cloth, 18% for every cloth-bound copy sold beyond the initial 10,000, and 10% for the paperback editions.

C.B. Van Niel

Despite his earlier claim that he would not feel confident in the company without Freeman directing it, Pauling continued to maintain a positive and productive relationship with his long-time publisher. In one particular instance, Pauling played an instrumental role in smoothing tensions caused by an unflattering review of a Freeman text. The review in question was authored by microbiologist C.B. Van Niel, whose highly critical assessment of Wayne W. Umbreit’s Modern Microbiology appeared in the widely read magazine, Science.

Prior to the review appearing in print, Van Niel had sent a letter to Bill Freeman warning him that the review would not be favorable, but Freeman had left the company by this point. His replacement, Stan Schaefer, didn’t see the review until it had been published. Once he saw the Science piece, Schaefer responded personally to Van Niel, writing that the criticisms had hit sales hard. Schaefer further speculated that Van Niel harbored a personal grudge against Umbreit and that this was the real source of the animus permeating the review.

It was at this point that Pauling came to Schaefer’s aid. He informed Van Niel that he personally had not found the book to be nearly as flawed as the review claimed and accused his correspondent of “malicious mischief,” stating that most of the errors that he attacked were simple and relatively common across publications.

Without waiting for Van Niel’s response, Pauling then wrote to Phil Abelson, the editor of Science, asking him to redact the review because it was disrespectful, incorrect, took sentences out of context, and was overly aggressive in tone. Seeing Pauling come to Umbreit’s defense, many other professionals in biology and bacteriology spoke out against the review, criticizing its focus on minor errors. More importantly, many within this group also chose to adopt the text despite its flaws.

To stave off future conflicts of this sort, Schaefer requested that, as a courtesy, drafts of reviews be sent to Freeman & Co. before publication, so that the company could prepare if the analysis was unfavorable. Pauling also asked Van Niel for his own annotated copy of the Umbreit text so that Umbreit could use it in his revision process.

When Stanley Schaefer promoted Bill Kaufman to president in 1969, he assumed the position of chairman, a post that had previously been occupied by Freeman himself. Kaufman opted for early retirement in 1971, reporting to Pauling that the timing felt opportune because the “fame” of the company was at an all-time high. He was also confident in the competence of the staff and its collective motivation to ensure the continued success of the company.

Pauling was also feeling bullish about the company’s prospects — so much so that he finally brought up an issue that had been troubling him for some time. Contractual modifications that Bill Freeman had instituted for the second edition of College Chemistry — modifications that lowered Pauling’s royalty rate — were presented as temporary changes needed to help grow the young company financially. When it was suggested, Pauling saw no problem with the change, so long as it was temporary. But, as far as he could see, the lower royalty rate had been applied to the third edition of College Chemistry as well, and Pauling came to feel that he was being taken advantage of. In a letter to Stan Schaefer he expressed his feeling that the agreement, as it was being continued, “might be said to have been obtained by fraudulent methods, involving statements to me that I think were untrue or at least misleading about the financial situation of the Company.”

Schaefer checked the royalty statements and concluded that Pauling was correct in his assessment. After apologizing and thanking Pauling for bringing the matter to his attention, he then set about calculating the difference between the royalties Pauling had received and the royalties that should have dispensed. Once done, Schaefer assured Pauling that the company would pay him $5,000 owed for the second edition of College Chemistry and $7,400 for the third. Pauling thanked Shaefer for his straight dealing and then requested that the company pay him interest at the rate of 7% on these remittances because they were late.

Filed under: Colleagues of Pauling | Tagged: Linus Pauling, Roger Hayward, Stanley Schaefer, W. H. Freeman | Leave a comment »