OAC students in the Chemistry Lab, 1916. Note the student in military dress – during Linus Pauling’s undergraduate tenure, two years of ROTC were required of all males enrolled at the College.

[Post 2 of 4 examining Oregon Agricultural College during the years contemporary to Linus Pauling’s studies there as an undergraduate. These posts have been written in celebration of the centenary anniversary of Pauling’s enrollment at OAC (now Oregon State University) in Fall 1917.]

In 1908, Oregon Agricultural College adopted a semester system, which remained in place until the quarter system was reinstated in 1919. To graduate with a degree, 136 credits were required, and though an OAC student could not major in any liberal arts discipline at the time, all four-year degrees did require classes in the liberal arts. Linus Pauling fulfilled this requirement largely through foreign language study, taking coursework in French and German throughout his time at OAC. In addition, all students were required to take a gym class as well as an additional class in “Hygiene.”

As a Land Grant school, OAC offered a rich and varied curriculum that offered opportunities for both degree-seeking students as well as those wishing to bolster their practical skill through shorter vocational courses. The College was organized into seven schools: Agriculture, Commerce, Engineering, Forestry, Home Economics, Mining, and Pharmacy. The College also offered an affiliated but financially self-supporting School of Music, which was created at the behest of OAC students in 1908.

Some of OAC’s schools offered a wide breadth of options for their majors while others, such as Pharmacy, focused on a sole course of study. In the main, however, the variety of classes offered for students in most disciplines was staggering. Perhaps unsurprisingly, this was especially true of Agriculture, which offered seventeen “areas of specialty,” or majors. Included were emphases in Animal Husbandry, Bacteriology (the forerunner to modern-day Biology), Botany and Plant Pathology, Farm Mechanics (now Bioengineering), Soils and Farm Management, and Zoology.

Engineering was another popular course of study, perhaps second only to Agriculture, at least among male students. Within the School of Engineering, majors included Civil Engineering, Electrical Engineering, Highway Engineering, Industrial Arts, Irrigation Engineering, and Mechanical Engineering. In addition, other Schools offered engineering-centric degrees that pertained to their respective fields. For example, the School of Forestry advertised a degree in Logging Engineering and the School of Mines housed both the Mining Engineering degree as well as the Chemical Engineering curriculum.

Linus Pauling entered OAC with a particularly keen interest in chemistry, but he could not major in the discipline as, per state edict, the only School of Science operating at the time was located at the University of Oregon. Instead, Pauling chose the next best option, chemical engineering, as administered by the School of Mines. As he began his introductory coursework, Pauling may have found the classroom to be a bit more crowded than did previous first-term freshmen — the OAC Barometer, reporting on a bump in Engineering majors, hypothesized an invigorated interest “due to the demand for engineers in military service.”

OAC Home Economics students posing with children outside of the Withycombe “practice house.”

Women at the college predominately gravitated towards Home Economics, though a smaller number sought out degrees within the School of Commerce, majoring, more often than not, in Secretarial Studies. The School of Home Economics was organized into four degree paths: Domestic Art, Domestic Science, Home Administration, and Institutional Management. Specific Home Economics courses included Home Nursing, Sanitation of the Home, Dress Making, and Costume Design. The school also offered a year-long vocational course to men in Camp Cookery.

For additional scholastic development, women seeking degrees could hone their domestic skills in the college’s “practice house.” Opened in 1916, the Withycombe House was made available to interested Home Economics students who lived in the building for two months at a time, rotating through a variety of assigned duties during that time.

As mandated by the Morrill Act of 1862, men attending the College – including those enrolled in shorter vocational courses – were required to participate in military training. A ROTC program was officially established in 1917, Pauling’s freshman year, replacing the Cadet Corps that had existed previously. By the time that ROTC was implemented, the military organization at the College consisted of “one regiment of infantry, a hospital corps, signal corps detachment, and a band of fifty instruments.” Heading into 1918, as the U.S. ramped up its involvement in the Great War, OAC became a military hub of consequence for the state of Oregon, a scenario that repeated itself in the early 1940s.

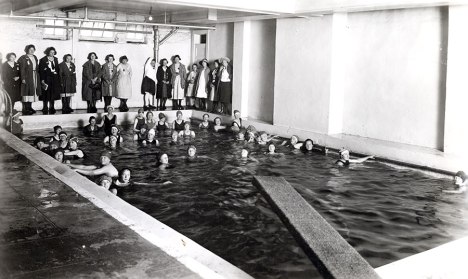

The pool housed in the basement of Shepard Hall, home to OAC’s YWCA operations.

Beyond scholarly inquiry and military training, the College strongly encouraged student involvement in extracurricular activities. This sentiment was echoed in advice that Pauling transcribed into his diary before he started college, wherein it was suggested that he “not take a number of extra [class] hours, but should try to do something for the school.”

OAC promoted a vibrant social environment for its students by fostering the creation and growth of student clubs and organizations. Most prominently, OAC was home to a number of Greek letter societies – one of which Pauling joined during his sophomore year – and other living organizations. Each dormitory and department as well as, in certain cases, specific majors, also sponsored their own club. As an incoming student studying in the College of Mines, Linus Pauling was naturally a member of the Miner’s Club.

The YMCA and the YWCA were also prominent organizations on campus, holding sway over many areas of campus social life and volunteerism. The YWCA, for example, organized the Campus Auxiliary of the National Red Cross so that the women of the College could fulfill their patriotic duty to “do their bit” in support of the war effort. To provide a base of operations for the YMCA and the YWCA, the College built Shepard Hall, which the two Y-organizations eventually shared with the Student Employment Bureau.

The College also housed organizations such as the Mask and Dagger – responsible for campus theatrical performances – the Oratorical Association, and the Intercollegiate Debate and Oratory organization. Likewise supported were location-based clubs that enabled students to connect with others who hailed from similar geographic backgrounds, especially California and Washington.

Central to the flow of information on campus were student publications, in particular the student newspaper, The Barometer. Published bi-weekly, students could find information in each edition on current events happening within the state and beyond, as well as notices of upcoming activities and meetings at the College. During Pauling’s time, the newspaper also regularly reported on humorous social slights in a column titled “We Have Observed That.”

This same lightheartedness permeated the final pages of the 1919 Beaver Yearbook in a section titled “The Disturber,” in which editorial staff ruthlessly poked fun at Greek letter organizations, other student publications, and the ROTC. While OAC prided itself on maintaining a serious scholastic environment and participated vigorously in the war effort, it is clear that the College’s students, in time-honored fashion, were intent on seeking out fun during their college years.

Through careful consideration and development of infrastructure and community principles, OAC provided a productive and agreeable setting for Oregon’s students to pursue a higher education. From diverse coursework to copious social opportunities, the College “within the vail of western mountains” provided students and professors with ample support to enrich themselves and their communities. These values clearly made an impact on the young Linus Pauling and continued to permeate his world view in the years that followed his departure from Corvallis.

Filed under: Pauling and Oregon | Tagged: curriculum, Linus Pauling, Oregon Agricultural College, ROTC |

Leave a comment