As the dynamics of Soviet dogma evolved, the enmity surrounding the so-called “resonance controversy” simmered down, and by the late 1960s Pauling had gone from being a disparaged name in Soviet chemistry to a respected scientist and much-admired advocate of nuclear test bans and international peace.

Pauling’s first visit to the Soviet Union in 1957 did a great deal to rehabilitate his scientific reputation among Soviet scientists. In his Pauling Chronology, Dr. Robert Paradowski notes that “Russia remind[ed] Pauling of Eastern Oregon, and the Russian people seem[ed] to him like Western Americans. ”

This visit was swiftly followed by his election to the Soviet Academy of Sciences in 1958 – along with Detlev Bronk, the head of the National Academy of Sciences, Pauling was the first American to receive full recognition from the Soviet Academy. Predictably, the honor was likewise enough to raise the eyebrow of the U.S. media, including the New York Times, which suggested that “it is impossible in today’s world position simply and naively to ignore the political implications” of the decoration.

Linus and Ava Helen traveled to the Soviet Union a second time in 1961 to attend the second centenary celebrations of the Academy of sciences, where they took the opportunity to deliver a handful of lectures, and to see more of the country, including a visit to Siberia and the shores of Lake Baikal.

The early 1960s also saw the reacceptance of Pauling’s formerly disgraced popularizer, Ia. K. Syrkin, back into the Soviet Academy of Sciences. By 1970 Pauling was recognized by the Soviet government for his peace activism with the Lenin Peace Prize, a honor bestowed upon foreign individuals conducting notable work in furthering international peace. Eight years later the Soviet Academy of Sciences decided to formally recognize Pauling’s scientific achievements by awarding him the Lomonosov Gold Medal, the highest award the Academy gave.

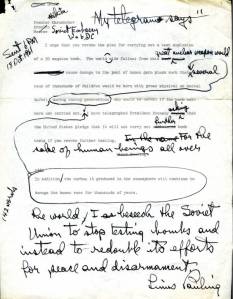

As might have been expected, Pauling did not hesitate to use his increasing fame in the Soviet Union to continue his advocacy for nuclear testing bans and better cooperation between the Soviet Union and the United States. His correspondence with Nikita Khrushchev, as contained in the Pauling archive, provides a revealing look into the increasingly intimate relationship between advocacy and diplomacy that helped define Pauling’s later peace work.

Learn more at the website “Linus Pauling and the International Peace Movement,” available via the Linus Pauling Online portal.

Filed under: Peace Activism | Tagged: Ia. K. Syrkin, Linus Pauling, Nikita Khrushchev, Robert Paradowski, Soviet Union |

[…] the Oslo Conference again nuclear testing, and continued to dialogue with both John F. Kennedy and Nikita Khrushchev about matters of nuclear weapons policy. The next year saw more of the same, including the famous […]